Essentials

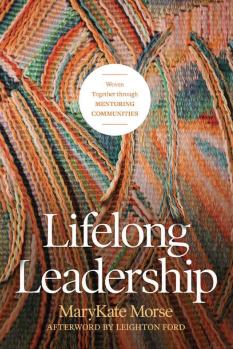

Book Review: Lifelong Leadership

- Details

- Written by: Wei-Han Kuan

Lifelong Leadership:

Woven together through Mentoring Communities

by Mary Kate Morse

Navpress 2020

‘When I look back at the past decade… this group is the thing that’s kept me in ministry.’ – Mentoring Community member, Australia

I know several individuals who would echo those precise words. Vocational gospel ministry is tough, perhaps the toughest gig in town. How we find encouragement and support along the way is a critical issue for the longevity of ministers and the progress of gospel ministry. Lifelong Leadership tells the story of one powerful solution. It declares its purpose up front:

‘…this book serves as a comprehensive, step-by-step, practical guide for experienced leaders in any country to learn how to create and launch a Mentoring Community.’

The book is part practice manual, part biography of a movement, part spiritual devotional. I loved it because I am part of its story and I’ve experienced the love and ministry of the authors and others involved in this work.

Part One outlines the urgent need for leaders and the urgent need of leaders for long-term spiritual mentoring.

The book tells the story of Mentoring Communities beginning with Leighton Ford and the forming of the Point Group. One of its members was and is Stephen Abbott, who was once the EFAC Victoria Training Officer and taught evangelism at Ridley.

My connection with Mentoring Communities began shortly after ordination when Steve invited me into what became the REFRESH Mentoring Community. We had each been his students at Ridley and were fresh out of college. He sensed rightly that the group would be critical to our longevity and health in ministry. We’ve tracked together for over a decade and are now spread across Australia with one in the UK.

Six years ago, I gathered younger clergy into the Resilience mentoring community, a third-generation group that is able to trace its links back to Leighton Ford.

We are part of a world-wide movement and international community of practice, the patterns and culture of which are the subject of the book. The aim is to draw together ministers who want to, ‘lead like Jesus, lead others to Jesus, and lead for Jesus’.

Groups come together annually in, ‘a safe space and time, with safe people’, to engage in a process of peer spiritual mentoring. The process includes practices that make up the chapters of Part Two of the book: Solitude, Prayer and Bible Reflection, Listening, Questions, Discernment, Group Listening Prayer. These chapters form the bulk of the book.

These practices have pushed me to lean into the immanence of God and the intimacy of the Holy Spirit’s knowledge of my life and care over me. In a Mentoring Community, we express God’s care for each of us in the context of the people of God. It’s an amazingly powerful and tangible expression of wise, prayerful, loving support – vital encouragement amidst the challenges of ministry.

Each of my two groups’ members would attest to that. Part Three reflects on the experience of Mentoring Communities – what are they like to be a part of? How are they gathered together and sustained? Read Lifelong Leadership to grab a sense of what Mentoring Communities might mean for you and your longevity and health in gospel leadership. If you’re a more senior leader, what might they mean for your capacity to multiply ministry and invest in a subsequent generation of leaders? What would EFAC’s ministry look like if Mentoring Communities proliferated among us?

(Feel free to chat with Steve or Wei-Han too.)

Wei-Han Kuan is the Director of CMS Victoria

Looking to the Bronze Serpent

- Details

- Written by: Rev Dr Fergus King

Henry Nouwen’s classic treatise on pastoral care, The Wounded Healer, highlighted an ambiguity of pastoral care: that many who care for others are themselves damaged and wounded. In doing so, he stripped away the pretension that carers must be perfect, superhuman beings, but rather could function effectively as agents of healing and transformation in spite of their own weaknesses and limitations. It is a book which enabled many carers to accept their own weakness and limitation and use their own suffering as a vehicle for healing. It is one of those rare books which stimulate a paradigm shift: a fresh approach to a longstanding phenomenon.

Henry Nouwen’s classic treatise on pastoral care, The Wounded Healer, highlighted an ambiguity of pastoral care: that many who care for others are themselves damaged and wounded. In doing so, he stripped away the pretension that carers must be perfect, superhuman beings, but rather could function effectively as agents of healing and transformation in spite of their own weaknesses and limitations. It is a book which enabled many carers to accept their own weakness and limitation and use their own suffering as a vehicle for healing. It is one of those rare books which stimulate a paradigm shift: a fresh approach to a longstanding phenomenon.

The abuse scandals within our church have stimulated another round of deep reflection, for which we must turn to scripture to assess. This potential of scripture has been recognised by, among others, Gerald O. West in his account of texts such as 1 Samuel 13:1-22 being used for social transformation when community workshops address violence against women in South African contexts. Here, the use of Scripture enables a subject usually considered taboo to be named and addressed. In this vein we turn to the episodes of the Bronze Serpent.

The Bronze Serpent: The Lifted Healer

And just as Moses lifted up the serpent in the wilderness, so must the Son of Man be lifted up, that whoever believes in him may have eternal life. (John 3:14-15, NRSV)

The character of the serpent may be immediately off-putting or negative a feature which serves well to illustrate the response that trauma may have had on the onlooker. As such it may provoke a reminder that the stuff of faith can be turned to harm. But, as the bronze serpent is an image of healing, it must be remembered that the ancients knew that medicine and poison are never far apart.

Derrida could identify three related characteristics: “not only pharmakos (victim or scapegoat) and pharmakon (medicine/poison), but also pharmakeus (sorcerer or magician)”. Indeed, antiquity knew multiple symbolic meanings for the serpent: sixteen which might be classed as negative, and twenty-nine as positive. The gospel belongs to a world which could use serpent symbolism positively. Indeed, it might be used to indicate any of divinity, life, immortality, and even resurrection: the bronze serpent may be understood as divine, a healer, or both. This is not as alien to our modern world as it might first appear: the caduceus (the staff of Hermes with intertwined snakes) remains, up to the present, a sign of healing.

This text provides a distinctively Christian focus for reflection on the nature of healing by drawing on an incident from the history of Israel (Numbers 21: 49) to articulate and understanding of the lifting up of Jesus. The event has a chequered reception within Judaic tradition: 2 Kings 18:4 describes the smashing of a bronze serpent by Hezekiah, whilst Wisdom 16:6 describes it as a “symbol of salvation”. John follows this positive assessment.

The verses highlight an analogy between Jesus and the bronze serpent: both are “lifted up”. The identification of Jesus as the Son of Man has already been made (John 1:51), and will be re-iterated (John 8:28; 9:35-37; 12:32-34). John makes belief in this lifting up of the Son of Man the basis for receiving “eternal life”, his preferred term for a superior mode of existence, distinguishable from natural life as now lived.

Whilst “lifting up” has frequently been identified with the Crucifixion, this identification does not exhaust its full range of meaning. The ambiguity of “lifted up” also stresses the idea of benefit, as the Greek hypsoun/hypsousthai may include a positive meaning: of being exalted. It thus may include both the notions of Crucifixion and “return to the Father in glory”. This allows Jesus’ “lifting up” to be a paradox: his debasement marks his exaltation or glorification.

A reading which uses the motif of “raising up” to connect Crucifixion and exaltation is to be retained. It gives the believer, or reader, confidence and hope because it is based on an event which has already taken place by the time of reading. John does not base hope on propositions about God but roots them firmly in the past events which he describes. The gospel, in its received form, goes even further, making these claims witnessed by the Beloved Disciple (John 21:24). These provide the stuff which makes confidence in Jesus’ identity and promises sure - not speculation, or mythic imagery alone.

Those who have experienced trauma because of the church, or themselves are wounded healers, are highly likely to look askance at it as a source of healing. The bronze serpent, too, initially seems an unlikely source of healing, given our innate instinctive reaction to snakes. However, gazing on the serpent who becomes identifiable as the crucified and risen Christ becomes the means to eternal life. Enabling this gazing in faith through the provision of resources and rituals which allow the Risen Christ to heal allows those who have been wounded to overcome their initial repugnance at the church and be transformed as they look beyond the church to Christ. The image also allows the church to remember its potential to repulse, and strive intentionally to replace the behaviours which provoke, enable, ignore, or deny abuse with those that are genuinely life-giving.

How are you looking to the lifted healer to achieve healing?

Fergus King is the Farnham Maynard Lecturer in Ministry Education at Trinity College, and previously missionary in Tanzania.

This study is an abridged academic article, references have been elided and available on request.

How Will We Make It?

- Details

- Written by: Rev Samuel Crane

How do we think we will make it? To be clear, I am not talking about salvation. I am talking about our expectations for life in ministry. After we graduate from college, get ordained or commissioned, brighteyed and full of hope at how God will work to build his church, what do we really think will happen?

How do we think we will make it? To be clear, I am not talking about salvation. I am talking about our expectations for life in ministry. After we graduate from college, get ordained or commissioned, brighteyed and full of hope at how God will work to build his church, what do we really think will happen?

We have a few options of course. We can look around and see ministers who have fallen into devastating sin, abusing money, power, and sex. Clearly not a highlight for the yearbook. If not that, we could burn out and retire within a few years, or maybe, just maybe, we hang in there and hope that Jesus comes back soon. Like next week?!

I recently saw a photo of thirty or so people whom I studied at theological college with. Some of them graduated with me or around the same time, all within the last 10 years. Of that group, one had to leave ministry because they were disqualified for moral failure, one left because the burden was too great and they burnt out, and four others were continuing on but badly bruised by the impact of other clerics. I count myself as one of the bruised. And of the thirty, I have lost touch with at least half so their stores are unknown to me.

What are we to do? How are we to survive ministry? Honestly, I don't even just want to survive, just hanging in there one more day. I want to thrive, and not because I want glory, but because I want my family to not see me as someone broken by what is the hope of the nations, and I don't want to see myself as another carcass behind someone else's bus.

So as I limp and seek Christ's healing, here are some things that I am learning. I don't have all the answers but I hope this is helpful to you.

ONE. Cling to Christ's call to follow him into salvation and TWO. Cling to Christ’s call to follow him into his mission. It is purely a gift of grace that I still call Jesus my king and saviour. We grieve as pastors when people share their stories of how the church has hurt them and how they have walked away. It is only God’s grace that my story is different. And not only has God kept me in the vine but he still calls me to lead his church, a wounded pastor. So with great thanks, I cling to this dual call. We don’t want to be one of those stories of pastors who walk away from Jesus, so with me, strive to nurture our faith, seek healing, grow in prayer and biblical devotion, and keep trusting in God to lead us in our ministry. If God can save Paul from a stoning and a shipwreck, what can a bully do?!

THREE. Gather people around you who are there to bless you. We know we can't do it alone but I think practically we can often live as if that is the case. Ministry is isolating in how it changes how we live and serve others in God's family, so we need to be proactive to gather people around us who are there for us, mentors, counsellors, peers, mental health professionals, etc. Right now I think the more the merrier!! So call your GP or EAP, get a mental health care plan and get support. Call a pastor who is a little bit older than you, a bit further along in their journey, and ask them to mentor you, to care for your soul.

One of God's great gifts to me is a peer group filled with other Gospel ministers. Some of us are in church ministry, some in campus ministry, and some in theological education. Our singular purpose is to be there with each other as we take the hits of ministry and to encourage each other to keep clinging to Christ and his call on our lives to lead his church and to proclaim the gospel.

If you don't have a peer group and a mentor, I can't impress on you how invaluable they are. It is priceless to know there are others who are with you, others who are praying for you, and that there are others you can go to and offload your situation without judgment or offence. I have ministered in a multi-staffed team and now on my own, and in each church, I have needed people outside of my ministry context to whom I can cry out, safe people who love me and are with me. And at times, this love has been hard truthful words that I didn’t want to hear. We need people who we can share our deepest struggles with so that the pulpit is not our moment of self-care but a moment of sharing how Jesus has triumphed (definitely needs to be past tense) over our scars.

Practically what this looks like in my peer group is that we go away on retreat each year to debrief our year of ministry, to pray deeply for each other, and to reflect on our ministry by discussing a helpful resource. We also share prayer points throughout the year for our ministry but mostly for each other in ministry, our own faithfulness, holiness, struggles, and of course joys, ministry isn’t all bad! At times we also call each other for counsel as we are confronted with challenges and help each other reflect in practice.

There is a joy that comes from fostering deep fellowship with others, a joy that is a comfort during the isolation and struggles of being a jar clay. So let’s carry this treasure together, for the glory of our Lord Jesus and for our joy and peace and thriving.

Samuel Crane is Priest-in-charge of St James Glen Iris, Victoria.

Who Comforts the Comforter?

- Details

- Written by: Rev Joel Kettleton

Recently, a cartoon popped up on my feed from one of the Anglican groups I’m in. The cartoon depicted a minister, alone at the front of the church building, slumped over, crying. The title of the post was ‘Who comforts the comforter?’. As I continued to notice the details within the picture, I also noticed the emotions that welled up in me: sadness, anger, confusion, and compassion. This minister, who is both surrounded by objects that proclaim God’s faithfulness and care, and who is sitting at the front of a building that has most likely been recently filled with people, is alone and broken. Why is that? What has led to this moment?

Recently, a cartoon popped up on my feed from one of the Anglican groups I’m in. The cartoon depicted a minister, alone at the front of the church building, slumped over, crying. The title of the post was ‘Who comforts the comforter?’. As I continued to notice the details within the picture, I also noticed the emotions that welled up in me: sadness, anger, confusion, and compassion. This minister, who is both surrounded by objects that proclaim God’s faithfulness and care, and who is sitting at the front of a building that has most likely been recently filled with people, is alone and broken. Why is that? What has led to this moment?

Burnout within ministry leaders has come to the fore in recent years, particularly in response to the impact of lockdowns and post-lockdown life on churches, as well as the increasing administrative load ministers are undertaking in response to policies to do with protecting vulnerable people and other compliance issues. There is an increasingly large pool of articles and resources explaining the phenomenon of burnout within clergy, how to care for ourselves, and how to build resilience in ministry. It’s encouraging that the Australian Church is having this conversation in the open. However, as I look around at how many of my colleagues in church leadership are not doing well, I wonder how many of them have had moments like the one in the cartoon.

A recent Partners in Ministry Webinar on avoiding burnout and building resilience in ministry stated that 25% of church leaders suffer from burnout, and that another 56% of leaders are at risk of burnout. When you think about numbers like that you may begin to feel similar emotions to the ones I had viewing the cartoon.

My first experience of burnout in ministry occurred 15 years ago when one of the teenagers in my church took their own life. The fallout in the local community was immense. For weeks I was always prepared to care for someone in grief. By the end of the month, I experienced a tiredness that was all consuming. For months I was emotionless: unmotivated and unresponsive to anyone or anything to do with ministry. When I went to a psychologist, the first thing they said was, ‘That makes sense – I see a couple of people in your position every year’. Perhaps you’ve heard of stories like this or experienced something similar.

Burnout can be broadly described as a psychological condition in response to prolonged stress within a role. It is particularly prevalent in people-oriented industries. There are three common dimensions of burnout: exhaustion, cynicism and detachment from the role, and a sense of ineffectiveness or lacking accomplishment. There are several helpful tools that can help identify areas of risk or signs of burnout, but even in naming those three areas above, my guess is that some people could identify they might be at risk.

So, who comforts the comforters?

The Anglican Church of Australia has mandated professional pastoral supervision for those in church leadership as part of its implementations of the recommendations from the Royal Commission into Institutional Responses to Child Sexual Abuse. The Royal Commission found that ministers had few structures of accountability in their roles, due partly to the structures of the Church, as well as the isolated nature of their work, resulting in ethical concerns for the welfare of those under the minister’s care, as well as their own welfare.

While leading the Church brings about a deep sense of joy and purpose within ministers it can also be incredibly isolating – both for those working as solo ministers as well as those leading team ministries. The introspective nature of ministry work – often done in the mind before it manifests amongst a congregation, and the role of a leader – with the weight of responsibility in decision making and pastoring, contributes to this sense of isolation.

Pastoral supervision is an intentional, boundaried relationship, where space is created to critically reflect upon the ministry practice of the supervisee. This space within pastoral supervision allows ministry leaders to openly share what has happened in their ministry with someone who understands, while being outside of their context.

One of the illustrations I share with new supervisees to describe what pastoral supervision is and its benefits is like the mudroom in a farmhouse. Having spent the last decade living in rural Tasmania, I was introduced to the concept of a room where you take your muddy clothing and footwear off before entering the home, clean and fresh. Pastoral supervision provides a supportive space where ministry leaders can critically look at their ministry – how it has affected them and how they might be affecting others, before continuing in their context. Research in burnout and ministry resilience states that one of the key components to combat burnout is a formal program of critical reflection that brings insight, leading to future impact. Pastoral Supervision provides this.

The good news for church leaders in the Anglican Church of Australia is that help is at hand. Through the rollout of professional pastoral supervision, there is a regular space for leaders to unpack the realities of ministry with someone who will listen, support, and gently challenge them. Those in Christian leadership understand the all-encompassing nature of ministry – the ups and downs, the absurd and the profound, and the impact it has on your personal life. It’s not only nice to have time where someone is there to pay attention to you and your context – it’s essential to being able to keep on doing it.

Top tips for ministry leaders receiving professional pastoral supervision:

- Make the most of the time – Supervision is not just another ‘tick in the box’. See it as crucial time for your well-being and development.

- Put the work in – Become reflective in your practice by noting what happens in ministry, bringing something ‘live’ to supervision, and committing to working on it afterwards.

- Be honest – A supervisor is only going to work with what you give them in a session. The more open and honest you are, the more room there is for God to work and change you.

Top tips for churches in supporting ministers in receiving professional pastoral supervision:

- Continue praying for leaders – Uplift leaders as they serve in their role, as well as the impact it has on them outside of ministry.

- Be generous – The minimum number of 6 sessions may not be the most beneficial experience of pastoral supervision for leaders.

Consider funding regular supervision sessions, as well as other professional development and self-care opportunities for ministry leaders.

Joel Kettleton is an ordained Anglican Priest. Having served in parish ministry over the last decade, in 2022 he studied a GradCerti of Professional Pastoral Supervision, and now offers pastoral supervision to ministers around the country. Joel has a deep passion to see the Australian Church grow, with a call to support Christian leaders. He lives in Melbourne with his wife, Kristina, and three children. To help keep happy and healthy, Joel enjoys playing music and trains in Brazilian Jiu Jitsu.

Don’t Get Sick, Get Supervision

- Details

- Written by: Rev Fiona Preston

My first career was in Fashion Design. I studied for four years and found a job through a friend designing children’s clothes for a company that supplied to Myer, Target and Big W. It was a steep learning curve! It started out with much excitement and enthusiasm as I used the skills I had learnt at TAFE and learnt new skills on the job about shipping, designing a year in advance, and looking at previous sales to dictate future styles. But nothing from my studies could prepare me for the emotional toll the job would have on me and the difficult personalities I would meet along the way. One manager I had was prone to throwing things and didn’t believe me when I came down with influenza: the real one that makes your body shake uncontrollably and binds you to your bed for a good week. There was very little trust in that workplace, a lot of gossip and much finger pointing when things went wrong. After four years I couldn’t take it anymore and after one particularly bad week I told my husband I was quitting…tomorrow! After leaving I had plans to create my own pieces of fashion so I went out and bought unique fabrics from fancy shops, and bought an industrial sewing machine. Sadly, I was exhausted and uninspired. All the joy and enthusiasm I began my career with was gone. I sold the sewing machine and I still have the bag of gorgeous fabric sitting in storage. I didn’t have the words for it at the time, but I was burnt out. I never returned to the fashion industry and the thought of sewing garments still fills me with anxiety.

My first career was in Fashion Design. I studied for four years and found a job through a friend designing children’s clothes for a company that supplied to Myer, Target and Big W. It was a steep learning curve! It started out with much excitement and enthusiasm as I used the skills I had learnt at TAFE and learnt new skills on the job about shipping, designing a year in advance, and looking at previous sales to dictate future styles. But nothing from my studies could prepare me for the emotional toll the job would have on me and the difficult personalities I would meet along the way. One manager I had was prone to throwing things and didn’t believe me when I came down with influenza: the real one that makes your body shake uncontrollably and binds you to your bed for a good week. There was very little trust in that workplace, a lot of gossip and much finger pointing when things went wrong. After four years I couldn’t take it anymore and after one particularly bad week I told my husband I was quitting…tomorrow! After leaving I had plans to create my own pieces of fashion so I went out and bought unique fabrics from fancy shops, and bought an industrial sewing machine. Sadly, I was exhausted and uninspired. All the joy and enthusiasm I began my career with was gone. I sold the sewing machine and I still have the bag of gorgeous fabric sitting in storage. I didn’t have the words for it at the time, but I was burnt out. I never returned to the fashion industry and the thought of sewing garments still fills me with anxiety.

In their book ‘Burnout: From Tedium to Personal Growth’ Ayala M. Pines and Elliot Aronson describe burnout as, ‘The result of constant or repeated emotional pressure associated with an intense involvement with people over long periods of time…Burnout is the painful realisation that they can no longer help people in need, that they have nothing in them left to give.’

Sadly, my story isn’t unique, burnout is very real and the price of burnout to self, family and community is high. As a now ordained Deacon working as a prison chaplain and Spiritual Director, God has been good and has certainly taken me on an interesting journey through life. In a way, I’m fortunate that I burnt out from the fashion industry and not from ministry – though it could easily happen. It’s very upsetting when someone burns out from working in Christian ministry. Where they were once full of joy and enthusiasm, they become fatigued, gloomy, fearful and resentful. Unfortunately, I know people who have burnt out and I am aware of others who are on the precipice of it.

One issue I perceive is that we start out our ministry vocation with great passion! Comparing our ministry to Jesus, Paul or other greats who have walked before us, who appear to be so self-sacrificing and sold-out that when we feel tired or weak, we berate ourselves for not being more capable. After all if they can do it shouldn’t we? Actually, we are all unique and our ministry settings and situations are unique too. As members of the body of Christ comparing our ministry output won’t benefit us and may bring more anxiety than anything else.

Another issue I observe is the toll of being a solo minister. As the number of ordained clergy decline and church membership lowers there is less opportunity to employ curates, deacons or assistants. If ministers don’t set good boundaries from early on and delegate to lay parish members, they can end up doing everything and being the sole solution to most problems in the parish.

These are just two areas I identify that can cause stress and pressure. So, what can help with all this? I believe one key answer is sharing our mental load with others.

Prioritising our mental health and wellbeing means we are putting in measures so we can last the long run in ministry. One way I encourage is to have a recurring monthly appointment in our calendar for supervision, counselling, or spiritual direction. Many dioceses are now providing pathways to subsidise supervision which will enable more people to afford this essential care and oversight. Unlike when we go to the doctor when we are sick, or to the physio when our body aches, supervision is something we can put into practice before we get too sick and achy and, is a means of prevention before we need intervention.

What does supervision look like? Professional Supervisor Emily Rotta, a registered supervisor and member of the ACA College of Supervisors says “In sessions, I create a supervision relationship based on trust and transparency. As well as providing an open space for learning and best practice which focusses on the supervisees self-reflective practices and wellbeing.”

Supervision should be a safe, confidential space where the wins and hardships of ministry can be aired and explored and where one should come away feeling heard and supported.

Let us strive to run the long race in ministry, be encouraged to find a supervisor and make an appointment today.

Fiona Preston ministers with MinisTree Bendigo and is a Spiritual Director.

Stress, Burnout, and … Creativity?

- Details

- Written by: Rev Ralph Mayhew

“What’s cracking? It’s Ralph Mayhew here and I’m a full-time minister, serving a merger church, in Burleigh, QLD and I have a YouTube channel on photography and filmmaking, which has nothing to do with my ecclesiological ministry!”

“What’s cracking? It’s Ralph Mayhew here and I’m a full-time minister, serving a merger church, in Burleigh, QLD and I have a YouTube channel on photography and filmmaking, which has nothing to do with my ecclesiological ministry!”

If you watch one of my videos, you won’t get that intro, but you’ll get something that feels just like it. I remember the day when I clicked the button that would send my first YouTube video live. It was a couple of years ago, and the torrent of 36 views that followed was inconsequential. It was a gamble to start my channel, as I wrestled with the question “Will this bring me more life or take it away?” This was the only question I needed to answer. I had a hunch it would, but the only way I’d know, is if I tried. I did try and it has, tenfold.

This question “Will this bring me more life or take it away?” is a dangerously underrated question we often feel guilty asking in the world of Christian leadership.

I sit with lots of new leaders, many of them young who are feeling tired, worn out, stressed, perhaps even angry, exhausted, frustrated and with declining mental health reserves. The common thread in every one of these scenarios is they are putting out more than is being poured in. Their life is being taken away, and not being replenished. They are gaining the whole world of ministry (only not really) and losing the health of their soul in the process.

“But I meet with God every day, I read his Scriptures,

I seek his will for my life and my ministry. How can I still be feeling like this?”

A valid retort, but unfortunately an incomplete one. As these words are expressed, Psalm 23 whispers to me “I will make you lie down in green pastures.” I often wonder if God is saying to this generation of Christian leaders, ‘you need to find a place where you are reconnected with where you came from. Where you find joy, meaning from being, express your creativity and aren’t held hostage by unrealistic measures.’

Of course, time alone in prayer, and Scripture study is imperative to our health as leaders, but the story is much broader and deeper than just this. Our story began with a creative God, who breathed us into existence. We could have looked like anything God desired, the result being we were inspired by his own image. In exercising his creative Spirit he produced us in the form we have.

The writer of Genesis declared: “So God created humankind in his own image, in the image of God he created them; male and female he created them.” (Gen 1:27)

We were created, we are created beings, by a creative God, who declares his creation to be made reflective of His image, a creative one! Do you see the common thread? We were made by the creative spirit of a creator God, to live a creative image, by creating. So why is this the first thing to be eroded in a leader’s

life as they step into the river of Christian ministry? Perhaps because the creativity the church requires from us (especially now); perhaps the time and energy we might otherwise invest in personal replenishing creativity, has been all but used up by the demands of ministry.

When I push back on those leaders and ask ‘what are you doing that is creative? That isn’t attached to any goal posts or key performance indicators, that brings you joy and causes your energy to be spent in a most wonderful way?” They nearly always look at me with loss for words, a lingering grief with a hint of intrigue. The intrigue comes from the invitation into creativity, which resonates with something deep inside them.

As the conversation ensues there’s always something that causes them to say “You know, I used to do that,” or “I’ve always wanted to learn about that or give that a go.” Those who follow through find greater balance, increased joy and a creative expression that repairs and sustains their soul like nothing else can. It’s as if they now get to enjoy the most painless and freeing therapy session, whenever they wish.

That’s why I’m on YouTube. That’s why I’m a photographer. It gives me life! It improves my relationships, my ministry, my energy reserves and my mental health.

Making a video, of which I have done a few times now, is a wonderfully creative experience. It starts with an idea, then develops into a plan, with a loose script, I then film and re-film, and sometimes, re-film again. Then we go to the editing room a process which has gotten longer and longer, correlating with the length of time I’ve been on the platform, and finally I export, upload and release it to the world.

My channel is about photography and filmmaking, which is the other creative pursuit I document with my videos. I call it therapy. Getting outside with my camera in creation. Accepting a challenge to capture something intricate, beautiful or bizarre. It enables who I am to be celebrated and expressed, in a way that doesn’t need to please those who have varied expectations of me (think: those you minister to).

I love those stages, all of them, because each, in their own way are creatively replenishing. Replenishing because I am exercising my creative muscle, outside of the need to please anyone or anything. It gives me life, it stretches my ability to think beyond constraints, it offers something that may help others, and it ushers me into wonderful connections and relationships with people who I wouldn’t have otherwise met.

I can spend my full day off, planning, photographing, filming, thinking and creating, and as a result I then move into the following week with far more energy and vitality than I had previously. I’ve discovered that when we take our cues from culture about what it means to replenish, binge watching Netflix on the couch, that the image of God within us is dulled.

But when we adopt the same stance that our creator God took, who is madly in love with us, we discover life, replenishment, strength, courage, hope, joy and creativity, all of which God then uses in our ministry.

I have also discovered that there is only one person who can truly give you permission to explore this for yourself. It’s you! And me now, too, I guess. No one else will be able to gauge or trust the incredible value a unique creative pursuit can have for you, but you can try it for yourself and see. My prayer is that you do!

Ralph Mayhew is the pastor at Burleigh Village Uniting Church and you can find him online at Ralph Mayhew Photography (http://ralphmayhew.photography/)

Art, Cars, Coffee, Mission, and Mental Health.

- Details

- Written by: Rev Adam Gompertz w. Rev Dr Chris Porter

A Chat with the Scribbling Vicar

Psychiatric nurse and car designer come historic car artist, Station Chaplain to Bicester Heritage, pioneer missionary, and minister to the classic car community through the REVS meetings and REVS-Limiter online group, the scribbling vicar Reverend Adam Gompertz talks faith, mission, and mental health.

Chris: Moving from nursing to car design, ordination, and now as a pioneer minister is a rather large series of shifts. How did that come about?

Adam: I grew up with parents who were vicars, but like a lot of vicar’s kids I didn’t really think of ministry, and ended up getting into the car industry via a long and protracted process via psychiatric nursing. Once I was in the car industry it was prompted through a period of redundancy in the 2008 recession. There wasn’t an angel standing at the end of my bed with a flaming sword, saying “It’s you, it’s you.” Rather it was more that we started looking and the doors kept opening. I was accepted for the selection course— which I liken to the SAS except with more cake and less diving through windows. But between selection and hearing back, I had started at Rolls Royce Motor Cars and really had to make a choice. But at that point I had no pioneer leaning at all. I thought I would be a vicar in a country church in rural England and that was it.

While in the car industry, I had a sense that when you went to theological college you left your old life at the door and walked into a new life and suddenly turned into a priest. The problem is that I could never leave the cars behind. I never quite fitted in that way. I still loved the cars, and the whole scene. During college I started reading works on missionality and church, like The Shaping of Things to Come, and that blew my mind. The picture of what ministry could look like, and what ministry needed to look like in the age in which we were living. From then on, I started thinking rather than walking away, what could I do to go back into that community as a priest. That really started my thinking.

Chris: The automotive industry and classic cars tends to be a far more diverse space than what we see on a Sunday. How did you end up being a clergyperson in that space?

Adam: When I went and did my curacy, in a very wealthy area, the vicar said you are going to have to deal with people driving around in Ferraris and Aston Martins, and I was like “sure, fine, no problem.” Back in 2014 I asked him to do a car show in the church. We had 28 cars, opened the church, served food, and made sure everything was free so that people didn’t think we were after their money. At the end of that someone said to me “you know this is only going to get bigger” and I thought “this is it, we are done;” but sure enough we doubled in size each time we held it. Yet it was tough to grow relationships with an annual event, so we moved to a monthly Cars and Coffee meet in Shrewsbury. That first REVS group has just grown from there, and quite naturally I just fell into this pioneer role as God opened the doors bit by bit.

I had spent quite a bit of time in my teenage years trying to marry having a faith and being a car fanatic. Can you be both? Because I thought that surely cars are very materialistic. Over these years I have come to a position that, yes, you can do both; and perhaps in the church we should stop dividing ourselves up into our work life and spiritual life etc. I feel just as called on a Sunday morning to be in a carpark peering into somebody’s engine bay as I do in a pew. I think it’s a by-product of our evangelical underpinnings, where we see God purely in terms of church, but He is out there doing stuff and calls us to join in; often in the most surprising places.

I have just as many encounters with God around cars as I have anywhere else. Because cars give space for a community to walk with people through the highs and lows of life, and for me that is my calling. Not so much to preach at people but called to walk with them, weep when they weep, and to celebrate when they celebrate; all with the perspective of God’s kingdom.

Chris: How have you found the reception of your faith and reflections on faith in such a secular space?

Adam: When I put things out, like a Fuel for Thought, there will be people in the group who are way off the spiritual radar, others who are curious, and others who are onboard. The challenge then is how do you talk about Jesus in a way that people won’t switch off,

but a way that puts it in their language. One of the things with REVS that I felt called to ask was “what does the kingdom of God look like in a car community?” For me, that is one of the key questions that I go back to. Aspects like radical generosity, compassion, healing, forgiveness, and wholeness. What do they look like in the car community? The Fuel for Thought reflections seek to do that, and to meet people where they are at.

Church language just doesn’t work in this space, people are so unfamiliar with it, or have a simplistic one-dimensional understanding. Instead of typical church language we talk about “rust,” and “restoration,” all grounded in the car stuff that we know and love, and from there we can ask questions.

It’s what Jesus did, taking the language of fishing, planting seeds, building houses—the language of his every day—and applied the gospel to what people are familiar with. With REVS we do a “Carols by Carlight,” and use metaphors of journeying, like the Pilgrim Tour along an ancient Christian pilgrim route in North Wales. I liken it to being bilingual, speaking the language of our host culture, and being familiar with the church and theological language.

Chris: One of the challenges with car culture is that there is often a self-reliance, a stiff upper lip, and people don’t want to talk about their struggles. How have you seen REVS speaking into that space?

Adam: I think that initially it is rooted in my own walk with mental health, in that I have struggled with anxiety and depression and obsessive-compulsive disorder for around 25 years now. It has become part of our life, as a family, and we have learnt to manage and live with it. Part of my ministry came from sharing that story, and from the fact that after a major breakdown I have had the sense of God restoring me bit by bit. I just started telling my story.

Psychiatric nursing gave me an awareness of mental health, but it was my own story and God’s restoration that really promoted it. REVS really is a story of God’s restoration, it’s not a story of my own ministry, because several years ago I really thought that I was on the scrapheap.

Telling my story was the first stage, and then meeting others with a similar story, paired with a general cultural willingness to start talking about mental health. COVID and lockdown certainly had a knock on effect with people’s mental health and gave space for talking. The REVS-Limiter online community itself was borne out of our shared lockdown frustration. Charlotte—my wife—asked me one day why I was grumpier than usual, and I said, “because I can’t get the car out and meet with others,” so she suggested taking it online. I remember thinking that if I get a few people watching along it would be amazing, and by the end of the first event we had almost 3000! We made sure we talked about mental health, offered prayer, and finished each event with a prayer of blessing. REVS-Limiter doesn’t hide faith away, instead people know that as a vicar I am probably going to mention Jesus at some point, and people are open to it.

Chris: The Barna group recently found that 42% of those in ministry have considered quitting in the past year alone. Pioneer ministry is often seen as this super high stakes environment. How has the REVS ministry been a blessing to your own mental health?

Adam: Like any kind of ministry, it has its demands, and it sometimes feels like we are just making it up as we go along. Some things work, and you are amazed; then other stuff won’t. There is a great deal of introspection, which comes with ministry anyway, but heightened because this is new and different, and a sense of wanting to do things right. All things which play into my anxiety. Here the artwork that I do is great, not just as a tool for starting conversations, but also to switch off and refresh myself. But I have to be careful with my art, that it doesn’t just become another ministry tool and kill my enjoyment of it. There is a challenge with having refreshment so close to ministry. It really takes some discipline, especially as the ministry keeps expanding.

Chris: What advice do you have for others who want to engage in pioneer ministry?

Adam: You can do the same with anything. People who run groups which are all geared around baking bread or making stuff to eat, others doing stuff with animals. Dog walking is a massive way to meet people and becoming a community of some kind. In some ways I am not doing anything radical or different, certainly not from Jesus did. I’m just doing it in a different context. With REVS we talk about being community, we aren’t a car club, but a community that is open and welcoming and allows people to celebrate their own piece of car culture. Just trying to model the kingdom of God in this space.

When I was first thinking about REVS, a friend of mine advised me to be straight with where you are coming from. Because there is nothing worse than going to something and finding that you have been pulled into something else. The bait and switch of “come watch a film… oh it’s a film about Jesus.” People know where I am coming from, and who I represent. Sometimes that busts their ideas about what a vicar represents. With REVS-Limiter we say that there will be faith posts there for you to think about and reflect on, if that isn’t your thing just pass on by, but there might be something to engage with. Being up front with it leads to things like being on a podcast and having the hosts open up about their own faith journey, or others praying for people who are struggling or have had their car stolen. We need to take faith into people’s lives and go be where they are at rather than expecting them to be where we are at. Like mental health it is all about just being honest and saying, “this is me.” When you are in that space, then get people around you. For so many clergy there is a sense that they are the only ones who do ministry. Particularly within some of our more middle-class churches we have inherited this model where people come, sit, and go and that is all their involvement. Actually, that is not the church that Paul was talking about or that Jesus started, where people came, got involved, became an active community, involved in every area of life. We have made it very personal and private, with the vicar doing all the ministry. It is little surprise that many get to the point where they just can’t keep going on like that. Certainly, in the UK we have significant clergy burnout, as there is no one to help and support. With REVS I was getting to the point where I realised that the ministry needed more than just me to be involved. I have a very good group of directors around me, who are keen to release me to do the bits that I am good at and know me well enough to support my mental health.

Adam Gompertz is Station Chaplain to Bicester Heritage, and @revslimiter on Social Media