Essentials

Not Rivals but Partners: Uniting Planting and Revitalisation for Kingdom Growth

- Details

- Written by: Bree Mills

In every generation, the Church is called to be both faithful and fruitful, anchored in the gospel and courageously reaching into a changing world. In the Diocese of Melbourne, this means we are committed not only to planting new churches in communities where people are not currently being reached, but also to revitalising existing congregations where the light of Jesus has grown dim. These two approaches are not in competition; rather, they are essential companions in our commitment to Kingdom growth.

Our ecclesial tradition reminds us that the Church is the Body of Christ—gathered and sent by God, sustained by Word, sacrament, and prayer. We are grounded in the historic faith and continually renewed by the Spirit to engage in God’s mission. This dual calling challenges us to hold together tradition and innovation, deep roots and outward reach.

A SHARED VISION: CHURCH PLANTING AND REVITALISATION

Church planting has gained momentum in recent years, and we have seen new communities flourish when formed with clarity of vision, cultural contextualisation, and missionally shaped leadership. Yet planting alone cannot address all the challenges we face. Many existing congregations are experiencing long-term decline, demographic shifts, or a loss of missional energy. These churches remain part of the Body, and to neglect them would be to neglect our calling to every member of it.

The Diocese of London has demonstrated that replanting into existing churches is among the most strategic ways to bring about renewal. They have shown that declining churches can become vibrant centres of worship, discipleship, and mission when they are entrusted to leaders with fresh vision, supported by a committed team, and encouraged towards renewal. This can be through intentional revitalisation, or replanting something new, while still caring for existing congregations. This is not about discarding the past but honouring it – hold tradition in one hand and bold hope in the other.

Such an approach echoes a deeply Anglican instinct: to renew without severing from our roots. The Church is not a static structure but a living body, shaped by Scripture and sacrament, and reformed over time by the Spirit. Jesus spoke of bringing out treasures both old and new (Matthew 13:52), and we are invited to do the same. Revitalisation and church planting are both treasures.

WHAT MIGHT A DIOCESAN STRATEGY ENTAIL?

If we are to take revitalisation seriously at a diocesan level, we must develop a strategy that is both theologically grounded and contextually responsive. Such a strategy might include:

1. Honest, Compassionate Assessment

Not every declining church is destined to close. Some are poised for renewal. Like Nehemiah surveying the broken walls of Jerusalem, we need leaders who can discern with courage and care where revitalisation is possible. Where is the Spirit already stirring? What might be possible with new leadership and a renewed vision for mission?

We need to honestly assess the needs of a church, which requires building a culture of openness and support rather than ‘shame and blame’ so that we can most effectively discern the best way forward.

2. Leadership for Ecclesial Renewal

We must invest in raising and releasing leaders who are equipped specifically for revitalisation. This form of leadership differs from that required in planting. It calls for high levels of emotional intelligence, spiritual resilience, adaptive capacity, and pastoral imagination. These leaders must be capable of walking with congregations through seasons of grief and change while inviting them into new life.

Training has historically focused on high levels of intellectual knowledge, or specific ministry skills (such as preaching), which while essential, are not the only skills needed. We need leaders with soft skills, relational skills, change management skills, cultural and situational awareness, who can care for and lead a community 3. Cultures of Collaboration, Not Competition Revitalisation and planting must not be siloed. They thrive when pursued in partnership, in part because sometimes the most effective form of revitalisation takes the form of replanting (often termed ‘repotting’). A healthy diocesan culture will allow for mutual learning, shared resources, and the cross-pollination of teams across these areas. A revitalised church may go on to plant; a planting team may help breathe life into an existing parish. We belong to one Body and we will each need to play our part to see the whole church built up into maturity.

4. Flexible, Sustainable Models

There is no one-size-fits-all approach. Some revitalisations will resemble grafts or replants. Others may be best served by forming networks with stronger parishes or through reimagined ministries that respond to the needs of their context or particular people groups. Our structures must serve our mission—not the other way around—and we must be ready to adapt as the Spirit leads.

The church in the book of Acts comes in many forms: larger public gatherings, smaller house-based gatherings and missionary bands. We need to be open to different models to reach different people in different contexts.

5. Prayerful Dependence on the Spirit

Ultimately, revitalisation and church planting are not the product of strategy alone. As Paul reminds us, “Though outwardly we are wasting away, yet inwardly we are being renewed day by day” (2 Corinthians 4:16). Renewal is God’s work, begun and sustained in prayer. As we root ourselves again in Scripture, sacrament, and the power of the Spirit, we can trust that God will bring life to new communities and renew life where there has been loss.

A VISION FOR THE WHOLE CHURCH

The future of the Church in our diocese will not be found in choosing between planting or revitalisation. It will be found in a generous vision that embraces both. We are called to plant and to prune, to graft and to grow—as God leads.

We are not preserving an institution; we are proclaiming a gospel. The Church—ancient and new, inherited and emerging—is the bearer of good news in our generation.

As we align ourselves with the Spirit’s work of renewal, we can trust that God will continue to raise up a faithful, courageous Church—sent out in joyful witness to the risen Christ.

Rev. Bree Mills is Canon for Church Planting and Revitalisation, Anglican Diocese of Melbourne.

A cultural change to evangelism: the election of Ric Thorpe as Archbishop of Melbourne

- Details

- Written by: Peter Adam

I read in a book on management that minor technical changes are easy to achieve, but cultural changes are hard to achieve! And if cultural changes take a long time to achieve in a church, they take much longer to achieve in a larger and looser structure such as a diocese. But cultural changes in a diocese have a great impact on local churches.

I read in a book on management that minor technical changes are easy to achieve, but cultural changes are hard to achieve! And if cultural changes take a long time to achieve in a church, they take much longer to achieve in a larger and looser structure such as a diocese. But cultural changes in a diocese have a great impact on local churches.

WHAT HAPPENED?

In this election, we saw a massive cultural change to focus on evangelism!

Who did we elect? 70% of the Melbourne Anglicans who were members of Synod voted for Ric Thorpe, an effective personal evangelist, experienced in planting churches with the gospel, and reinvigorating churches with the gospel, the gospel of God’s free gift of grace and love in the Lord Jesus Christ. We voted for an Archbishop to transform the culture of the diocese and our churches from maintenance to mission, and a cultural change to prioritise evangelism!

Read more: A cultural change to evangelism: the election of Ric Thorpe as Archbishop of Melbourne

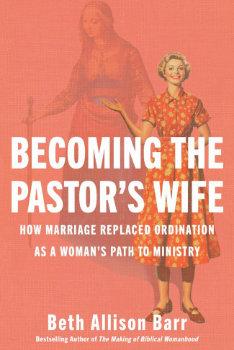

Book Review: Becoming the Pastor’s Wife

- Details

- Written by: Alexandra Phillips

Becoming the Pastor’s Wife

Becoming the Pastor’s Wife

BETH ALLISON BARR

Brazoz Press, 2025

Reviewed By Alexandra Phillips

Herself a pastor’s wife and historian, Beth Allison Barr challenges the contemporary Southern Baptist Convention (SBC) notion of ‘pastor’s wife’ from within. Her book is a timely, welcome contribution to conversations on the role of women in leadership. Barr questions the wisdom of narrowing the pastor’s wife role to supporting a husband’s ministry, and argues its recent evolution is associated to the decline of female ordination. Whilst offering a leadership opportunity for some women (albeit subordinate), the pastor’s wife role deauthorises women’s independent leadership. Barr persuasively objects to this being considered a biblical role, noting the Bible’s silence on the role performed by wives of ministering husbands, like Peter’s wife. Barr also protests the claim that alternative church leadership roles for women are nonbiblical, pointing to women with authority like Prisca and Junia, whose ministry shows no signs of dependence on a husband in ministry. Likewise, she reveals historical women in church leadership. Barr builds her case compellingly through chapter after chapter of illustrative stories arising from an eclectic mix of history, a survey of ‘pastor’s wives’ literature and her personal experience, inviting the reader’s reactions along the way.

As a historian, Barr complexifies statements about women’s ordination across the ages. She notes its contemporary understanding is a recent development, disagreeing with powerful SBC leaders like Al Mohler (president of the Southern Baptist Theological Seminary). Though Barr’s flow within chapters is occasionally convoluted as she overdoes suspense or draws out her evidence, she ably holds a wide gaze on history by contrasting women’s ministry and ministry titles from different time periods. From the early church-fifth centuries, she uses archaeological evidence to tell of women in church leadership, including performing the eucharist. Next Barr concludes mid-seventh century female superior, Milburga, had a comparable position to a bishop, in her rule over a double monastery (monks and nuns). Then Barr neatly explores how ordination reforms in the 10th-12th centuries linked it to the powerful position of performing the eucharist, requiring a sexually pure unmarried male priest. As medieval priests hardly pursued sexual purity, the result was the debasement of women. Later, though male protestant reformers married, they kept a position of ‘masculine authority’ gained from having an exemplary wife, which led to the origin of the subordinate pastor’s wife position.

Barr then rigorously examines SBC history, demonstrating the influence of particular people, events and resolutions that rapidly and recently turned the tide on the SBC position. Where it previously recognised women’s ministry, both through ordination and just payment, it then defunded churches with female pastors. Barr records Dorothy Patterson’s sway, pushing the complementarian agenda for the white evangelical pastor’s wife, through seminary lessons in which wifely submission was presented as the woman’s highest calling (including training on packing a husband’s suitcase, housekeeping and sex). Far from agreeing that women’s pursuit of church leadership is culturally influenced, Barr suggests capitalism and the 19th century rise in domesticity of women’s work as influential to the SBC notion of the pastor’s wife. As ‘godly woman’ became equivalent to ‘good wife’, she draws the parallel to ‘women in ministry’ becoming ‘wife of a minister.’ Barr clearly establishes links between the growth in submission language in pastor’s wives’ literature and the complementarian Danvers statement (1989), Piper and Grudem’s book Recovering Biblical Manhood and Womanhood (1991) and the ‘submission statement’ (1998) added to the SBC confessional document. She uncovers how the recategorization of ministry workers for tax exemptions led unwittingly to controversy over women’s ministry titles, positions and payment. Thus, as women’s independent path to ministry became more difficult, the pastor’s wife model of service ‘covered the absence of female pastors.’ This resulted in the loss of authority of women’s leadership, and women’s leadership becoming subordinate by definition.

Though Barr regrets the bleakness of the SBC trajectory she uncovers, she closes with stories of hope from church history and the not-too-distant SBC past. She also provocatively suggests that if the white church’s pastors’ wives modelled themselves on the black church for a change, this might lead to a truer opportunity for women to minister with spiritual authority and recognition.

Becoming the Pastor’s Wife is a stimulating read, informing how recent developments have shaped the (widely influential) SBC complementarian concept of the pastor’s wife. This serves as a case study beyond the SBC, and should prompt the church to re-evaluate biblical foundations and historical claims made of the ‘pastor’s wife’ and women in church leadership.

Alexandra grew up in Chile in a missionary family as a pastor's daughter. Since moving to Melbourne, she has studied history, literature, theology and teaching. She is a pastor's wife and mother of two daughters.

7

Bible Study:No Marriage in Heaven: Luke 20:27-38

- Details

- Written by: Stephen Hale

At present we’re all incredibly conscious of the importance of upholding the Bible’s teaching on marriage as between a man and a woman. In the midst of this on-going struggle, I was struck recently when reading again Jesus’ teaching in Luke 20:34 and 35 that ‘there is no marriage in heaven’.

The context is the Sadducees coming to Jesus with a loaded question. ‘Some of the Sadducees, who say there is no resurrection, came to Jesus with a question.’ (27) The Sadducees know exactly what they’re doing. They are simply attempting to bait Jesus with a classic “what if” question!

So, Jesus - Moses wrote for us about how to handle a situation if a married man dies without producing children. The wife is to remarry one of her brothers-in-law in order to have a child. But, what if this happened, and a woman remarried brothers and never had any children with them, who would she be married to in the resurrection? (28-33)

The Sadducees refer to an old Mosaic law that had hardly ever been enacted. It’s a trick question because they didn’t believe in the resurrection. There is also a pastoral dimension to it. Who will carry on the family name?

Jesus, as was his wont, didn’t engage with the question. He goes straight to the heart of the matter. And, what a surprising response it is.

Jesus replied,‘the people of this age marry and are given in marriage.But those who are considered worthy of taking part in the age to come and in the resurrection from the dead will neither marry nor be given in marriage,and they can no longer die; for they are like the angels. They are God’s children, since they are children of the resurrection’. (34-36)

As Jesus puts it, people in this age are involved in marriage. As we know it is still one of the great moments of most peoples’ lives.

But, and it is a big but, in the age to come there will be ‘neither marriage nor being given in marriage!’ What is going on here? Isn’t the life to come a sort of never-ending extended family get together?

He goes on to say, ‘and they can no longer die; for they are like the angels. They are God’s children, since they are children of the resurrection.’

Jesus here is giving us a unique insight into the life to come. As Christians we do indeed believe in life after life. If we are God’s children, then we are children of the resurrection. Just as Jesus died and rose again, we believe we will die physically and after death we will be raised again physically. Life after life starts today with Christ and continues on into eternity. Our physical death is but a stepping-stone into a whole new future. To reinforce this point he refers to the patriarch Moses.

But in the account of the burning bush, even Moses showed that the dead rise, for he calls the Lord “the God of Abraham, and the God of Isaac, and the God of Jacob”.He is not the God of the dead, but of the living, for to him all are alive.’ (37-38)

What can we learn from this fascinating dialogue?

We see that Jesus believed in and taught of a forthcoming physical resurrection. We see that he believed that in the life to come there will be continuity with this life. We will be recognisably ourselves. Yet there will be discontinuity. At present we live by faith and not by sight.

In the life to come we will be with Jesus face to face.

At present we pray and read the Scriptures and in this way we believe we commune with him – we talk with him and he speaks to us.

In the life to come he will speak directly and we will respond in praise and wonder.

More specifically we can see from Jesus’ teaching here that marriage is a gift from God given for human flourishing. It is given for mutual companionship but also for human reproduction. It is for the good ordering of human community.

Yet we also see that it will be unnecessary in the life to come. In that future and eternal life we will experience human community as a part of God’s renewed people dwelling on God’s renewed planet. All of the things that currently divide us will be overcome - racial tension, hatred, hostility, war, rage and malice. We won’t be defined by our sexuality, and we will enjoy true intimacy one with book reviews another. Young and old, men and women and those who are uncertain. The rich and poor and the seemingly significant and seemingly insignificant. The rage and anger that is so much a characteristic of our age will be no more. The tension within the church over issues related to marriage and sexuality will also be no more!

Does this somehow dishonour and diminish marriage in our current lives? I think not. As it says in the Prayer Book, marriage between a man and a woman is to be honoured by all and no one should enter into it lightly or selfishly, but responsibly and joyfully, with mutual respect and the promise to be faithful. At the same time, it also means that we don’t build our entire world around our marriages. We commit to and invest in it, but we also need to keep it in perspective. Friendship with others is vital for a healthy marriage. Christian worship and service should be key features of family life. Christian community should be an important commitment. Churches should model the life to come by being places where people of any background are welcome. Single people shouldn’t ever be viewed as second-class citizens but should find rich friendship and love in the context of Christian community. None of this can be assumed and requires generous hearts.

This is an amazing vision of true human community. So how can we ensure we are a part of it – both today and in the future?

Jesus put it this way – ‘those who are considered worthy of taking part in the age to come and in the resurrection from the dead’ (v.35)

How can we be considered worthy?

Surely, none of us are worthy. Especially, of the age to come, of the resurrection from the dead. Every time we share in Holy Communion we acknowledge our unworthiness. We reach out hands to receive bread and wine. In this way we remind ourselves, personally and collectively, that it is only through trusting Jesus that we can enjoy new life today and the hope of a glorious future in his eternal kingdom. Jesus himself deems us worthy of taking part in the age to come, worthy of the resurrection from the dead!

Our ongoing challenge is to help as many people as possible to discover how to be worthy.

Bishop Stephen Hale is Acting General Secretary of EFAC Global.

EFAC Queensland Update

- Details

- Written by: Lynda Johnson

Anglican evangelical ministry across Qld has a rich history. Rev Jeff Roper came to Brisbane to start a CMS branch at the end of the 1950s, and with the CMS League of Youth, reaped the fruit of the Billy Graham Crusades. There has been faithful evangelical ministry for decades, holding strong in the face of increasing liberalism and at times, significant progressive activism. EFAC in Qld has long been the place for lay people to find their home. There are more lay members than clergy members, which has always been a great blessing. In recent years, the membership of EFAC has grown, and it is hoped this will stimulate even more strategic connection and creative thinking for future Gospel impact.

Anglican evangelical ministry across Qld has a rich history. Rev Jeff Roper came to Brisbane to start a CMS branch at the end of the 1950s, and with the CMS League of Youth, reaped the fruit of the Billy Graham Crusades. There has been faithful evangelical ministry for decades, holding strong in the face of increasing liberalism and at times, significant progressive activism. EFAC in Qld has long been the place for lay people to find their home. There are more lay members than clergy members, which has always been a great blessing. In recent years, the membership of EFAC has grown, and it is hoped this will stimulate even more strategic connection and creative thinking for future Gospel impact.

Following the gradual change within Melbourne Diocese over the last 30 years, my prayer is that there might be similar transformational change across Queensland, and particularly in Brisbane Diocese.

The two dioceses in the country which are at the forefront of the liberal/progressive growth are Perth and Brisbane. While some smaller Dioceses are also liberal/progressive, they don’t have as much influence because of their size. Perth and Brisbane have significant influence.

Queensland has three Dioceses – Brisbane, Rockhampton and North Qld. It is great that for more than a decade, the Bishops of Rockhampton have been evangelical. The Diocese of Nth Qld, while geographically large, has a proportionately small number of parishes. In both Nth Qld and Rockhampton Dioceses, BCA is providing wonderful ministry in many rural and regional areas, and there are great growing evangelical churches in the cities of Cairns and Townsville, including one associated with the Diocese of the Southern Cross.

Here is a more detailed snapshot of the Brisbane Diocese, noting that these figures are as accurate as possible with the information available.

Currently there are 158 active clergy across the Diocese of Brisbane. 23.4% of those would align with the evangelical end of the spectrum. While Diocesan statistics would give a larger number, I estimate the number of parishes in the Diocese to be 117, as many (particularly in the western region) are unviable. 22.2% of those 117 are led by evangelicals.

Both clergy and parish figures are close to 25%, which is encouraging. While one would expect that these figures might equate, evangelical parishes are more likely to have more than one stipended clergyperson, which is the case in at least 3 parishes.

The Diocese is divided into southern, northern and western regions. The Southern Region has the strongest representation with close to 30% of parishes clearly evangelical or led by evangelicals. The Southern Region is also where two churches associated with the Diocese of the Southern Cross began, and both they, and those who chose to remain, are now doing well. The Northern Region used to be stronger than it is now, but due to purposeful attrition of evangelicals over the last 25 years, previously strong evangelical parishes are no longer that. There are currently 5 parishes led by evangelicals which equates to 10% (down from previously 11 parishes which would have been 23%). Due to the smaller number of viable parishes in the Western Region, just over 30% are led by evangelicals.

It is also significant that there are vacancies in parishes that are seeking a clear evangelical leader (currently approx. 8), and with some retirements in the next couple of years, these figures will change.

These figures should encourage us. Please pray that EFAC across Queensland will continue to shine a light for Godly gospel ministry, that brings many to Christ.

Rev. Lynda Johnson is the Chair of EFAC Qld.

Partnering Together to Reach a City: The Trinity Network Story

- Details

- Written by: Paul Harrington

ADELAIDE IS A GREAT PLACE TO LIVE

ADELAIDE IS A GREAT PLACE TO LIVE

When you think about Adelaide, what comes to mind? The City of Churches? The AFL Gather Round? Wineries? Pie floaters (an Adelaide cuisine involving a meat pie floating in pea soup and smothered in tomato sauce)? When I ask some of my friends this question, they say, ‘Not much!’. I’ve lived in Adelaide most of my life and love it.

But here is the thing you really need to know about Adelaide and South Australia – we are gospel poor. A tiny percentage of the population attends church regularly, and few of these are in evangelical churches. Like every other state in Australia over the last 60 years, mainline churches have experienced a huge drop in attendance and membership. Our city and state are full of people who are spiritually lost and in desperate need of the gospel.

Read more: Partnering Together to Reach a City: The Trinity Network Story

The City on a Hill Story

- Details

- Written by: Luke Nelson

I remember the very first time I went to the church, and the feeling I had. I was working as a graphic designer, and I’d be contacted to make a logo for this new church. It was called ‘Docklands Church’ then, because it met in the newest part of Melbourne, the Docklands precinct, and I went there one Sunday, as a designer trying to understand his client. It became something much more personal than that, though, because almost as soon as I entered the space, I felt like I’d entered something I wanted to be a part of – something that God was going to work in. I’ve been there ever since ...

I remember the very first time I went to the church, and the feeling I had. I was working as a graphic designer, and I’d be contacted to make a logo for this new church. It was called ‘Docklands Church’ then, because it met in the newest part of Melbourne, the Docklands precinct, and I went there one Sunday, as a designer trying to understand his client. It became something much more personal than that, though, because almost as soon as I entered the space, I felt like I’d entered something I wanted to be a part of – something that God was going to work in. I’ve been there ever since ...

The story of that church, which would soon become City on a Hill, is a remarkable story of God’s grace. Planted by just a small group of people in 2007, it has become a movement of churches, with 11 churches now spread along the eastern seaboard of Australia, and an average weekly attendance of 3300. Currently, City on a Hill has three more plants to launch in the coming months, with a vision and prayer to plant 50. In a time of decline for the Australian church, it stands out as a sign of grace – a work of God that has touched the lives of many and has the potential to be a great encouragement to God’s people across our nation.