Essentials

Book Review: The Coming of the Holy Spirit

- Details

- Written by: Matt Jacobs

The Coming of the Holy Spirit

Phillip Jensen

Matthias Media, Australia, 2022

Reviewed by Matt Jacobs

Having become a Christian as a teenager in the mid-90’s, one of the biggest debates I had to navigate was over the person and work of the Holy Spirit. Some of my Christian friends spoke about the Spirit a lot — the amazing things that happened at their churches, and the experiences they claimed to have. Other Christian friends rarely spoke about the Spirit — their focus was all on Jesus and the Bible. What stood out to me was the tension, and sometimes outright hostility between those two groups. The big questions for me weren’t just, “who is right?”, but more personally, “what if I don’t feel anything particularly ‘spiritual’ in my life? What if I don’t have ‘spiritual’ experiences… am I missing out on something? Am I not really a Christian?”

How I wish I had a book like Phillip Jensen’s The Coming of the Holy Spirit to help me at the time. Though at first it felt a little disappointing: where’s the controversy? Where are the spicy take-downs of views he disagrees with? Wisely, right in the introduction, Jensen points out that ‘these issues may be so important to us, or may loom so large in our vision, that we can’t see around them to what God has actually said to us about the Holy Spirit. We may be so intent on solving our current problems and answering our burning questions that we fail to hear what God is saying to us though his word.’ (p7). And that’s the real highlight of this book.

Jensen begins by carefully walking through Jesus’ promise of the Spirit in John 14-16, then explores the arrival and world mission of the Spirit in the book of Acts, then moves on to the work of the Spirit in the Christian life by exploring the New Testament letters. With all of that important information as a foundation, the book then turns to address many of those hot-topics, in short appendices such as ‘baptism with the Spirit’, ‘speaking in tongues’, ‘guidance’, and ‘spiritual warfare.’ The result is a surprisingly gentle, yet incredibly clear and helpful book that carefully untangles much of the controversy, and settles on the wonderful truths that God has revealed in his word.

Two particular highlights for me were Jensen’s insights on the fruit of the Spirit (chapter 21), and the contrast between the ‘unspiritual’ and the ‘spiritual’ churches (chapters 23-24).

On the fruit of the Spirit, Jensen acknowledges the temptation we might feel to skip over the things that seem mundane, onto the more ‘controversial, exciting or glamorous aspects of the Spirit’s work.’ But to skip the fruit of the Spirit is to miss the vital, transformative, and truly miraculous work the Spirit produces in every Christian life (p254). The normal Christian life of submitting to the Lord Jesus and growing in Christlikeness is fundamentally and powerfully spiritual.

This is what I needed to hear more of in my youth! In contrasting ‘spiritual’ and ‘unspiritual’ churches (Ephesus and Corinth), Jensen points out that, ‘strangely to our ears, the most ‘charismatic’ church in the New Testament is in fact the most unspiritual. The church over whom most has been written on charismatic questions in modern times was in its own time viewed by the apostle not as a beacon of spirituality, but carnality’ (p283). That’s an insight I’d never noticed before! And again, ‘In their unspiritual minds, the Corinthians failed to understand that character is more important than competence, convictions are more important than curiosities, caring for others is more important than consoling oneself, and edification is more important than experimentalism’ (p305).

In summary, The Coming of the Holy Spirit is a clear, faithful, and gentle book that aims to listen to the wonderful truths that God has revealed about the person and work of the Spirit: that He himself dwells in our hearts forever, and grows us up in the image of Christ, by his Spirit.

The Reverend Matt Jacobs is the youth minister at St Jude’s Bowral, NSW.

Book Review: Timothy Keller: His Spiritual and Intellectual Formation

- Details

- Written by: Rhys Bezzant

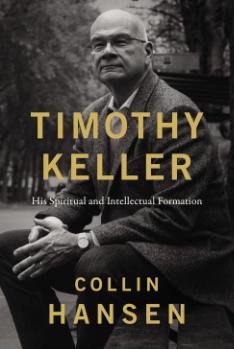

Timothy Keller: His Spiritual and Intellectual Formation

Timothy Keller: His Spiritual and Intellectual Formation

COLIN HANSEN

HarperCollins Religious US, 2023

REVIEWED BY RHYS BEZZANT

God in Gotham? It wasn’t too long ago that the ideas of thriving Christian ministry and downtown New York City were poles apart. No new church had been built in Manhattan for 40 years, that is until 2012 when Redeemer Presbyterian Church opened a new building. Of course, several of its campuses scattered around the city still rent premises. Indeed, one of their plants meets in the auditorium of the New York Society for Ethical Culture, a 19th century atheist society which is happy to rent out their lecture theatre οn Sundays. But today in some circles, New York has become synonymous with refreshed ways of engaging post-Christian culture. If it is possible there, it is possible anywhere. The leadership provided by Tim Keller at Redeemer in NYC has been game changing.

In his recently published biography, Collin Hansen has written a magnificent survey not essentially of Keller’s life but of the intellectual and spiritual influences which profoundly shaped him. It was truly absorbing. We learn about his education, mentors, and capacious reading. These took a bookish undergraduate, who grew up in a legalistic Christian home, and made of him a leading apologist, evangelist, and pastor in the later 20th and early 21st century. To be honest, I was sceptical of the project to publish a biography not a year after Keller’s death from pancreatic cancer in 2023. But it succeeds brilliantly because of its modest aspirations. A journalist, Hansen’s prose was crisp, the chapter and section divisions roughly following Keller’s career were helpfully focused, and his conclusions judicious. A full-scale biography awaits.

Keller became a Christian and cut his teeth in student ministry with the Inter-Varsity Fellowship at Bucknell University in Pennsylvania during the late and turbulent 1960s. He trained for the ministry at Gordon-Conwell in Massachusetts, not long after the amalgamation of the two schools (incidentally led by former Ridley principal Stuart Barton Babbage). Perhaps surprisingly, he then took up a Presbyterian pastorate in a working-class town, Hopewell, Virginia, whose claim to fame was advertised on its road sign: “Welcome to Hopewell, chemical capital of the South.” His professorial style was successfully matched to a social demographic hungry to know the Scriptures. He learnt how to communicate in new ways. He was subsequently called to teach preaching at Westminster Seminary in Philadelphia, after which he took up the reigns of a church plant in Manhattan in 1989, and stayed there for the remainder of his ministry life. His impact in Australia has been significant, for the church-planting organisation City to City was his brainchild.

Hansen does well not just to name the thinkers who have influenced Keller, but also summarises their theological commitments and outlines the story of their intellectual transmission. Keller’s legalism was transformed by reading Luther on the nature of grace, and he read the Puritans voraciously to discover how they understood the dynamics of the spiritual life. One of his most significant theological interlocutors has been Jonathan Edwards, 18th century pastor in Massachusetts whose project was to present the Christian faith using the category of beauty and thereby to address the human head, and heart, and hands together. In our fragmented world, this vision of harmony has proved particularly useful in Keller’s engagement with culture.

After his wife Kathy introduced him to the writings of the Inklings, Keller lived in the worlds of Narnia and of the Rings. These fuelled his commitment to the imagination as a strategy to renew society, and to refresh the church’s engagement with the cities of this world around it. Indeed, Kathy had a correspondence with CS Lewis from when she was a young girl! Many lecturers impacted Keller, for example Ed Clowney, Elisabeth Elliot, Richard Lovelace, and RC Sproul. His early Arminian sentiments were replaced with more self-consciously Reformed commitments during his theological education. In later life, he became friends with sociologist James Davison Hunter at the University of Virginia, with whom he investigated how any social movement might make an impact in the late modern world. The answer: networks. Keller was good at this.

His theological style was irenic and coalition building. No wonder he helped found the Gospel Coalition. His extraordinary church-planting and church health manual, Center Church, amply demonstrates his spiritual and ecclesiological vision. He wanted to join doctrinal clarity, personal piety, and cultural engagement, which together would shape the church’s witness and outreach. His theoretical and practical approach to diaconal ministries, in Hopewell or in Manhattan, was a significant element in his missional thinking. Of course, Keller’s prodigious output in publications is matched by his homiletical legacy. He did not set out to be a megachurch pastor, but perhaps that is at the heart of his success. He glories in the gospel of Jesus Christ, which “provides a nonoppressive absolute truth, one that provides a norm outside of ourselves as the way to escape relativism and selfish individualism, yet one that cannot be used to oppress others” (p250). We need the insights Keller gleaned from his reflection.

This was first published in The Melbourne Anglicans

The Reverend Canon Dr Rhys Bezzant is senior lecturer in Church History and dean of the Anglican Institute at Ridley College Melbourne and has recently been announced as the new Principal of Ridley College from 2025.

Spiritual Stress in Ministry

- Details

- Written by: Richard Harvey

Spiritual Stress in Ministry

Spiritual Stress in Ministry

I must apologise that it has taken me 2 years to respond to the important issue in Essentials, Summer 2022 on stress in ministry. The emphases on supervision (Preston, Kettleton), a supportive community (Morse) and looking to Jesus (King) were very helpful. However, I was surprised by a glaring omission. No-one noted that we do not minister in a spiritually neutral environment. Comer quotes Willard that ‘Hurry is the great enemy of the spiritual life…’ (p 17). By contrast, the NT would affirm that spiritual evil is. Consider the following.

- In the OT, there are less than 10 references to spiritual evil such as unclean spirits. By contrast, most books in the NT contain references to evil spirits. The exceptions would appear to be Titus, Philemon and 2 and 3 John.

- In Mt 6:13, we ask God to deliver us not from some sort of generalised evil but from ‘the evil one’, Satan.

- In the OT, spiritual evil can still appear in God’s presence in heaven eg. Job 1-2 and Zech 3. In the NT, all recorded interactions between deity and spiritual evil happen on earth; the most obvious being Satan tempting Jesus (Mt 4 etc). Despite Revelatrion being filled with scenes of heaven, there is nothing similar, most likely because evil has been expelled from heaven (Lk 10:18, Rev 12:9). While the timing of this is heavily disputed, I believe that it happened around the time of the Massacre of the Innocents (Mt 2).

- While Satan is called ‘the accuser of the brethren’ (Rev 12:10), his accusations in Job and Zechariah are unsuccessful and he makes no recorded accusations in the NT. As though an all-knowing God needs the prince of evil to accuse God’s own people! There may be some irony in calling Satan an accuser: a prosecutor who cannot make a charge stick.

- While the OT is filled with warnings against idolatry and the NT does warn against idolatry (1 Cor 10, 1 Jn 5:21, etc), the most severe warnings are against evil itself (1 Pet 5:8 ‘Resist him [the devil]…).

- In summary, there has been a big change from the OT to the NT. Evil is still very real and malicious but can no longer access heaven so all its fury is directed against God’s people. This is a particular problem for evangelicals as we want to help people move from the kingdom of darkness to the kingdom of light (Col 1:13, 1 Pet 2:9, etc). Evil does not take this at all well and if we are not obedient to what the NT says about resisting evil then our marriage partners, our families and ourselves will be targets.

What should we then do?

1. A necessary first step is to remove our cultural blinkers which say that this sort of thing does not exist in Australia. It most certainly does. Or, that evil was so decisively defeated at the cross that it is no longer a threat. The NT reached its final written form decades after the first Easter and still includes the most graphic warnings about evil. The cross provides the tools for dealing with evil and we have a responsibility to use them.

2. Our theology must be Biblical, in particular our belief in Jesus’ redemptive death and bodily resurrection and the gift of the Holy Spirit. If you have a face to face confrontation in the early hours of the morning with an unclean spirit, you cannot say to them, ‘Liberal theology says that you don’t exist.’!

3. Unconfessed sin and unforgiveness weaken our spiritual authority and thus our ability to resist evil. We need to ask the Holy Spirit to reveal these things to us and then deal with them.

4. We must check our obedience to the fourth commandment to honour parents, which is the first one with a promise (Eph 6). This requires honouring parents, repenting of any sin against them and renouncing their sins. I have seen this lead to visible, overnight healing without that healing even being prayed for. This is vital where parents and other ancestors have been involved in activities inconsistent with the gospel.

5. I am also concerned that accounts of defeating evil in Jesus’ name are derided as ‘war stories’ (thankfully not in Essentials). When I started as an aged care chaplain, we had a couple of apparitions which made one corridor unusable by staff at night. Answering residents’ buzzers then required a much longer route, where any delay could have serious even fatal consequences. The other chaplain and I sat in the chapel and said that these things could either come to us and explain their right to be there or go straight to Jesus, never to return. We never saw them again. This was a valuable demonstration of Jesus’ authority over evil, Arranging supervision and supportive communities must never take the place of obeying the NT’s clear instructions on resisting evil. We can do both and a good place to start is to write down every NT command about resisting evil and make sure that we are being obedient. It is also vital that we ask God to guide us to someone with experience in this area as mistakes can be costly. CS Lewis warned us many years ago of two equal but opposite dangers – either being obsessed with evil or completely ignoring it. Neither is helpful but if we are willing, God can open our eyes to this whole realm and show us his authority over evil.

Revd Dr Richard Harvey.

Associate minister Holy Trinity, Terrigal

Bible Study: The Transfiguration: Have We Missed the Point?

- Details

- Written by: Kym Smith

The Transfiguration: Have We Missed the Point?

The Transfiguration: Have We Missed the Point?

(MATTHEW 17:1-8; MARK 9:2-8; LUKE 9:28-36)

How wonderful was the transfiguration; in view of three of his disciples, Peter, James and John, Jesus was transfigured and met with two, similarly glorified giants of the faith, Moses and Elijah. The two men spoke with Jesus about his ‘exodus’, his departure via crucifixion which he was to accomplish in Jerusalem, to which he had set his face (Lk 9:51). The disciples had the added witness of the Father’s voice confirming that Jesus was, indeed, his beloved Son. That is how we have always understood the transfiguration, but have we missed something? This article suggests that we have missed something, and not just something; if correct, we have missed the main point of that amazing event.[i]

The proposition here is that the reason for Moses and Elijah’s appearance was not primarily to encourage Jesus towards the cross. They may have done that but given that darkest of deeds that he was facing, even those great men could not provide the level of encouragement he needed. The task given to Moses and Elijah was to greet Jesus and, perhaps, to open up the topic (of which Jesus was already aware – e.g. Mt 16:21; Mk 8:31; Lk 9:21-22). Without negating all that those men represented in the Law and the Prophets, however, they were, essentially, the welcoming committee; their task was to usher Jesus in to the only One who could encourage him sufficiently, the One who from all eternity planned that he should go to the cross, his heavenly Father.

Jesus invited his inner three disciples to witness what was designed for them to see. What they did see – not only Jesus glorified but Moses and Elijah glorified with him – and what they heard, the voice of the Father, would have buoyed their witness and carried them through much suffering in their lives and ministries (2 Pet 1:16-18).

Being transfigured and tasting something of the glory which he had with the Father before the foundation of the world (cf. Jn 17:5) certainly would have been a help but, again, that was not the primary purpose for Jesus being glorified. Rather, he was transfigured to clothe him appropriately to go before his Father “…who dwells in unapproachable light’ (1 Tim 6:16).

BACKGROUND INFORMATION

If we understand Eden, the garden of God (Ez 28:13), not just as a productive plot but the sanctuary of the Lord, the place he provided so that those he made in his own image could meet and fellowship with him, then it must have been a holy place, radiating with the glory (i.e., the holiness} of God (cf. the tabernacle [Ex 40:34-38] and Solomon’s temple [1 Ki 8:10-11]). In that case, Adam had to be sanctified before he could dwell in the garden/ sanctuary. Made outside of the garden (i.e., to the west of it – Gen 2:8), Adam was clean (in the biblical sense – Lev 10:10) and without sin or fault. However, clean was not sufficient to dwell with the Lord, he needed to be holy, but only God is holy. To enable him to enter Eden, then, the Lord breathed into him the breath of life (Gen 2:7; cf. Jn 20:22). This was not just air, if it was that at all, but the Holy Spirit (Heb. And Gk., Spirit=breath=wind.[ii] Receiving the Spirit, Adam was sanctified and the suggestion here is that he was clothed with glory (as per the transfiguration). Only after this was he placed in the garden (Gen 2:8).[iii]

When Moses asked to see the glory of the Lord, the Lord – no doubt the pre-incarnate Son – told Moses that no one could see his face and live (Ex 33:18-20). No one could look on the fullness of his glory, his holiness made visible, and survive it. We know that after Moses was allowed to see the tail end of the Lord’s glory, his skin shone (Ex 34:29). It may be that something of the Lord’s glory flowed over to the prophet; it is more likely, however, that Moses was granted the glory he needed so that he could safely see what he did of the Lord’s glory, receding as it was (Ex 33:21-23).

For the faithful who remain to see the Lord when he returns in glory (Mk 13:26), they will need to be glorified to meet him. To be confronted with the Lord in glory and not share his glory would be terrifying (Rev 6:12-17). In his first letter, John says that when the Lord appears, those who are children of the Father will see him (the Son) ‘as he is’ (i.e., in glory). How is it that they will be able to do that? They will be able to do that because they ‘shall be like him’ (1 Jn 3:2); they, too, will be glorified, ‘in the twinkling of an eye’ (1 Cor 15:51-53; Phil 3:20-21).

They will continue in that glory into eternity as they dwell with the glorified Son (Rev 1:12-16) and ‘the Father of lights’ (Jas 1:17).

The point of this is that to come into the presence of the Holy One, one has to be holy (Heb 12:14) and, as creatures, we need the God who is holy to provide that.[iv] If we return to the transfiguration, even the Son of God could not be presented to the Father without being clothed in glory. He may have been without sin but he came ‘in the likeness of sinful flesh’ (Rom 8:3) and the likeness of sinful flesh was not appropriate to go before the Father (cf. the man lacking the wedding garment – Mt 22:11-14).

The transfiguration, then, as wonderful an experience as it was for the disciples to witness, as useful as a reminder of his glory that it was for Jesus and as encouraging as those two giants of the faith may have been, the occasion was not primarily for those purposes. It was to make Jesus presentable so that, facing the horror of the cross, he could go in to the Father and receive the encouragement he needed to face it unflinchingly,[v] encouragement only the Father could provide.[vi]

EVIDENCE FROM THE SEQUENCE OF EVENTS

The sequence of events must have been something like the following.

Jesus took Peter, James and John to the top of a hill to witness what he knew was about to take place. Having reached the summit, Jesus was praying alone in anticipation of the imminent encounter and, as he did so, he was transfigured (Mt 17:2; Mk 9:2-3; Lk 9:29). With the disciples watching on, Moses and Elijah ‘appeared to them’ (Mt 17:3; Mk 9:4; Lk 9:30-31). The two men materialised; they stepped from the heavenly realms into this physical world[vii]. The disciples were terrified as they were confronted with the radiant holiness of God but, wanting to be useful, Peter offered their services to assemble some makeshift dwellings (Mt 17:4; Mk 9:5-6; Lk 9:33).

We must note here that it was as Jesus, Moses and Elijah were conversing together that the bright cloud appeared; not until after they had been speaking did it come and overshadow them (Mt 17:3-5; Mk 9:4-7; Lk 9:31-34).

That much was amazing and could have provided some encouragement before the ancient pair stepped back into the unseen spheres and Jesus’ glory faded. But the cloud which was apparently unnecessary for the appearing of Moses and Elijah and, surely, unnecessary for their disappearing (cf. Lk 24:30-31), came and embraced the whole party. The cloud represented the coming of the fourth (or seventh if we include the disciples) and main character, the Father.[viii] The voice from the cloud (Mt 17:5; Mk 9:7; Lk 9:35) did not necessarily mean that the Father was only meters away but it certainly revealed whom Jesus had entered the cloud to see.

Luke indicates that they all entered the cloud (Lk 9:34) but if that were so, the three disciples would have remained at its outer edges. Again, in Luke, just before the cloud arrived, we are told, ‘…the men were parting from him’ (Lk 9:33). Was that the three men parting from Peter (and the others) or Moses and Elijah parting from Jesus? If it was the former, the Old Testament saints were escorting Jesus into the cloud and so, to the Father. If the latter, the two were either preceding Jesus, perhaps to ‘announce’ him to his Father (not that the Father would have needed any introduction) or leaving him as he went before the Father alone.

At that moment, to the disciples at the fringes of the cloud, the Father spoke from the cloud, “This is my Son, my Chosen One, listen to him” (Lk 9:35). From this point, after falling on their faces terrified, the disciples slept (Mt 17:6); no doubt it was a God-induced slumber (cf. the guards of Mt 28:2-4; Acts 5:17-23 and 12:5-19).

How long they slept they would not have known. What was happening in the heavenlies was according to a different time scheme but the disciples dozed for as long as it took for Jesus to complete his audience with the Father, to return to the mountain top (possibly escorted), for the cloud to be withdrawn, for Moses and Elijah to exit and for Jesus’ glory to fade.

When it was appropriate (he may have spent more time in prayer), Jesus woke the disciples (Mt 17:7). Because it was a divinely induced sleep it seemed to them to have taken no time at all and so they were surprised when they looked up and all was as it had been before Jesus was transfigured (Mt 17:8; Mk 9:8; Lk 9:36).

SUPPORT FROM EYEWITNESSES (2 PET 1:16-18)

In his second letter, Peter reported that ‘…we were eyewitnesses of this (Jesus’) majesty’ (2 Pet 1:16). The use of ‘we’ here is significant. By the time he wrote (probably mid to late 64), Peter knew his own time was short (2 Pet 1:14) and James was long dead, he was executed by Herod Agrippa in AD44 (Acts 12:1-2). The ‘we’, then, must have meant him (Peter) and John. Were the two apostles working in collaboration at that time? If so, it was known to his readers.

What is particularly significant in Peter’s account is that he did not mention Moses and Elijah. If the main reason for the transfiguration was for Jesus to meet and be encouraged by those two men, the apostle was strangely silent about it. Not mentioning them suggests that their appearance was not what the event was about. Peter may not have recorded that Jesus was taken in to see the Father but he does – to the exclusion of Moses and Elijah – mention that Jesus ‘…received honour and glory from God the Father’ and that the Father audibly bore witness to his Son. Peter’s silence must be accounted for.

Clearly, the transfiguration was primarily about Jesus and his Father.

CONCLUSION

As encouraging as our understanding of the transfiguration has been with Jesus encountering Moses and Elijah, what he required was more than a conversation with those great men. Only the Father could give him the love, the comfort and the resolve that was necessary. Having received all that he needed from the Father, Jesus, laying aside his glory again (cf. Phil 2:5-8), descended from the mountain, strengthened and emboldened to continue to the cross.

Kym Smith has worked in Adelaide as a parish priest and as chaplain in both school and hospital settings. Now retired, he is enjoying more time investigating a variety of biblical and theological issues and publishing his findings.

Footnotes

[i] If what I am suggesting that we have missed is correct, then from the earliest times we have missed what the transfiguration was all about. Because it is such a major matter and makes so much sense of the event, the fact that the commentaries (at least the ones I have looked at) are silent on it can only mean that we have not seen it

[ii] Humanity was made to be in-dwelt by the Holy Spirit; it is part of what it is to be made in the image of God.

[iii] Eve, having been sanctified in Adam, was also clothed in glory (i.e., our primal parents’ nakedness in the garden/sanctuary was not the nakedness they later experienced, as have all who followed – Gen 2:25; cf. 2 Cor 5:1-5). The truth of this ‘garment’ of glory is reinforced by the fact that when Adam and Eve rejected the holiness given to them, when they listened to another voice and embraced evil (Gen 3:1-6), God withdrew from them his Holy Spirit and, with that, stripped away the glory. Now, in their dread-full nakedness, they tried to cover themselves but fig leaves were no substitute for the glory of God (Gen 3:7). Without that glory, without holiness, they could not remain in the garden/sanctuary and were expelled (Gen 3:22-24).

[iv] By God’s grace, we who are in Christ have already been sanctified but what we are speaking about here is not where we stand by faith but actually standing in the visible presence of the God of glory.

[v] It is often said that Jesus did ‘flinch’ in Gethsemane, that he was hoping for some way other than the cross when he asked his Father to ‘remove this cup from me’ (Lk 22:42). But not so; in the garden his soul was “…very sorrowful, even to death” (Mk 14:34). With the weight of the sin of the world crushing him, his concern was that he would die in the garden and not reach the cross; it was that ‘cup’ (‘hour’ in Mk 14:35) that Jesus wanted removed. His prayer was answered, the agony was not reduced but an angel was sent from heaven to strengthen him through it (Lk 22:43-44, see also Heb 5:7).

[vi] Was the Lord’s caution to Moses (Ex 33:20) applicable for the Lord himself appearing un-glorified before the Father?

[vii] Not that the spiritual/heavenly realms are not substantial for those who dwell there: note in 2 Corinthians 5:1-5 the ‘buildings’ they inhabit compared with the ‘tents’ in which we of this age dwell (see also 2 Cor 12:2-3). Though not yet ascended and glorified, Jesus would also step from the unseen realms into the seen in his post-resurrection appearances (e.g. Jn 20:19, 26).

[viii] The bright cloud must have been hiding the Father or, at least, an open entrance into the realms of glory and so, to the Father. A cloud often revealed as it concealed the glory of the Lord, declaring that the Lord was present (e.g. Ex 34:5; 40:34-38; 1 Ki 8:10-11; Acts 1:9).

Evidence and Faith

- Details

- Written by: Paul Barnett

Evidence and Faith

Evidence and Faith

My aim in this essay is to reflect on Paul as the earliest evidence for the birth of the church. His encyclical to churches in Galatia (central Türkiye) is his earliest written text and the earliest historical reference to Christianity. With less probability some argue for a date a few years later, although this doesn’t affect the force of my argument.

In this letter we have detailed accounts from his persecution of the church in c. 34 to the writing of the letter in c. 48 in Antioch in Syria. In between those dates we learn of God’s call to the persecutor to become the proclaimer of the Son of God among the Gentiles.

The former Pharisee who had attempted to destroy the church in Jerusalem became the most famous proclaimer of the Christian message, establishing churches “in an arc from Jerusalem to Illyricum.” This persecutor-becomeproclaimer is a fact of history, scarcely able to be denied.

His surviving letters are testament to his radical volte-face.

POSTMODERNISM

For many years now western culture, our culture, has been deeply influenced by “Postmodernism.” Back in the early 1980s a Professor of English Literature told me that the postmodern way of looking at life was going to change our culture. It will be about subjectivity, she said, how I feel, how I see things. The notion of objectivity, of what is there, will give way to personal feelings as the dominant source of reality. Postmodernism reinforces the self, the “me first” mindset. It runs contrary to the idea of God-given love, a way of life that is unselfish, “otherscentred.” These were our culture’s (more or less) agreed values before the rise of Postmodernism and its child, Woke.

EVIDENCE

Evidence is fundamental to life — juries and judges determine guilt or innocence based on sworn evidence; doctors base diagnosis and prescription on blood tests and scans; engineers and architects construct buildings based on surveyors’ precise measurements; the list goes on. The objective realities of daily life challenge the core assertions of Postmodernism. It is right, however, that evidence is challenged, to bring us closer to the truth. Otherwise, politics and ideology get in the way. Freedom

of speech is important.

EVIDENCE IN GALATIANS

Dates are important for evidence. The Galatians letter is informative.

33 The year of Jesus’ crucifixion and resurrection.

34 Paul persecuted believers in Jerusalem.

Outside Damascus God “called” him to preach his Son among the Gentiles.

36/7 He returned to Jerusalem now as a believer, lodged with Cephas, “saw” James.

Assisted by dates from Luke 3:1-2, Acts 18:1, and Galatians 2:1 we calculate that Paul launched his persecutions in the year 34, that he was in Damascus-Arabia-Damascus 34-36, that he returned to Jerusalem in 36/7, and moved to Syria-Cilicia in 37.

His Letter to the Galatians is his defence against ultraconservatively Jewish Christians in Jerusalem who sought to discredit his message of “grace” to Gentiles and overturn his influence among the Galatians.

AD 34 PAUL ATTEMPTED TO DESTROY THE CHURCH Paul was a distinguished younger scholar in Jerusalem.

I persecuted the church of God violently and tried to destroy it. I was advancing in Judaism beyond many of my own age among my people, so extremely zealous was I for the traditions of my fathers. Galatians 1:13–14

Paul’s parents brought him as a teenager from Tarsus to Jerusalem and enrolled him in the school of Rabbi Gamaliel, the greatest scholar of that generation.

Paul, the young rabbi, was distinguished in and “zealous” for “the traditions” of the great rabbis from earlier generations. He was also a “man of zeal,” a zealous persecutor of the church, which he attempted “violently” to “destroy.”

- He had participated in (possibly led?) the stoning of Stephen for blasphemy.

- He was the high priest’s “hatchet-man” in the flogging of Christians in the synagogues in Jerusalem to drive them from the city, which he did.

- Then he was sent by the high priest to round up and extradite believers from Damascus.

PAUL, CALLED BY GOD TO PROCLAIM HIS SON AMONG THE GENTILES

Paul reminds the Galatians of the astonishing fact of his “calling” from learned young scholar and violent persecutor to an apostle spreading the message about Jesus to the nations of the world:

But when he who had set me apart before I was born and who called me by his grace, was pleased to reveal his Son to me, in order that I might preach him among the Gentiles… Galatians 1:15–16

He re-tells his story: the astonishing volte-face of the violent young man. Outside Damascus God intervened to reveal to Paul that Jesus was not a false Messiah but the Son of God, whom Paul was now to “proclaim among the Gentiles,” that is, throughout the Roman world.

AD 34-36/7 PAUL A WANDERING FUGITIVE

He adds

I did not immediately consult with anyone; nor did I go up to Jerusalem to those who were apostles before me, but I went away into Arabia and returned again to Damascus. Galatians 1:16–17

Note the sequence (covering 3 years):

Jerusalem

Damascus

Arabia (i.e., Nabatea, capital Petra)

Damascus

Jerusalem (where he met with those who were “apostles before [him])”

Evidently Paul began proclaiming this message and was constantly on the move to evade capture. By referring to “apostles before me” Paul understood himself also now to be an apostle, one “sent” by God, bearing the authority of God.

AD 36/7 PAUL IN JERUSALEM

Then after three years I went up to Jerusalem to visit Cephas [i.e., Peter] and remained with him fifteen days. But I saw none of the other apostles except James the Lord’s brother. (In what I am writing to you, before God, I do not lie!) Galatians 1:18–20

Chronology is critical regarding evidence. When he says, “after three years I went up to Jerusalem” we are now in the year 36/7 (counting part years as full years, as the Jews did).

So, in the year 36/7 (only 3 to 4 years after Jesus) we learn:

Cephas (Peter) was the head of the church in Jerusalem

James the Lord’s brother was there, now a believer, 2nd leader after Cephas

And that there were “other apostles”

Notice what was in place in the year 36/7, back-to-back with Jesus, 33:

The church of God (an institution) 1:11

Cephas the leader 1:18

James, brother of the Lord, 2nd in charge 1:19

Apostles (a group) 1:19

These are definable entities that were there in 36/7, but most likely going back to Jesus. The historical figure of Jesus was followed immediately by the birth of the church. Not years after, but immediately (50 days) after.

PAUL WITH CEPHAS AND JAMES IN JERUSALEM

Notice that Paul “stayed with” with Cephas in Jerusalem for 15 days. Paul had opportunity to learn extensively about Jesus: his disciples, his teachings, miracles, death, resurrection.

Notice, too, that in Jerusalem he “saw” James, brother of the Lord? From James, younger brother of Jesus, Paul had opportunity to know about the boyhood and early manhood of Jesus.

Thus, from James and Cephas Paul had opportunity the learn about Jesus in continuity, from boyhood, to adulthood, to his baptism, to his call of the twelve, to his miracles, teachings, his trials, the Last Supper, his crucifixion, and his resurrection.

Rudolph Bultmann, possibly the most famous New Testament scholar in the first half of last century, said that Paul only knew about Jesus as a mythical, heavenly ahistorical figure. Paul’s connections with James, brother of the Lord, and Cephas, leading disciple of the Lord tell a different story. Like many, Bultmann was controlled by his existential philosophy, not history-based evidence. It has taken decades to dislodge Bultmann’s influence, thanks mainly to his fellow-German, Martin Hengel.

We see how much “raw” history emerges from Paul’s defence to his critics? Furthermore, he must be careful since his critics will be quick to fault him.

It is likely that while in Jerusalem Paul “received” the Last Supper “tradition” that he was to “deliver” later to the churches he established.

THE CHURCHES IN JUDEA

There is more:

In 36/7, before Paul left Jerusalem for Tarsus in Syria and Cilicia he observes: Then I went into the regions of Syria and Cilicia. And I was still unknown in person to the churches of Judea that are in Christ. They only were hearing it said, “He who used to persecute us is now preaching the faith he once tried to destroy.” Galatians 1:21–26

By the year 36/7 there were now churches in the wider province of Judea. This diaspora of believers was the result of Paul’s earlier persecutions in Jerusalem. Not only were there disciples in the capital Jerusalem, but they were also scattered outside the capital. These churches had been formed by Christians in Jerusalem who had fled from Paul.

Note their words,

“He who used to persecute us is now preaching the faith he once tried to destroy.”

In other words, in that year 34 the church’s “faith” was there as an entity to be destroyed. Paul had attempted to destroy both the church of God and its faith, its doctrine.

It so happens that Paul quotes some words that sound like a faith statement, one that Paul may have learned from Cephas, James, and other apostles in Jerusalem. This is not certain but is at least probable.

But when the fullness of time had come, God sent forth his Son, born of woman, born under the law, to redeem those who were under the law, so that we might receive adoption as sons, and because you are sons, God has sent the Spirit of his Son into our hearts, crying, “Abba! Father!” Galatians 4:4–6

In these few words Paul makes a “faith” statement:

- That is Trinitarian: The “Abba Father,” his Son, and the Spirit of his Son

- That is fulfilment-focused: “when the fullness of time had come”

- That is “incarnational”: God sent forth his Son, born of woman, born under the law

- That is redemptive: to redeem those who were under the law

- That is adoptive: that we might receive adoption as sons

- That is Holy Spirit-centric: God has sent the Spirit of his Son into our hearts, crying, “Abba! Father!”

It is likely that Paul’s words resembled the “faith” of the church in Jerusalem that he had attempted to destroy.

From whom did he learn it? Most likely from Cephas.

EVIDENCE FROM GALATIANS

What we have here in Galatians, this earliest of letters, is evidence.

- Of an institution, the church of God, that Paul had attempted to destroy

- Of that church’s faith, likely trinitarian, that Paul had attempted to destroy

- Of believers also in Damascus to be arrested, as inferred

- Of its leaders Cephas with whom he stayed, and James, brother of the Lord

- Of the church’s office bearers, the apostles

- Of churches scattered from Jerusalem in Judea

This is evidence that isn’t set out to be evidence for us, but for Paul’s congregants in Galatia, but which, notwithstanding, proves to be evidence for us. It is not a “gospel,” a narrative to tell the Jesus story. That is another historical-literary genre.

PAUL HAD TO BE METICULOUS

Evidence emerges incidentally from Galatians, even accidentally. Therefore, it is almost certain factually. Paul is appealing to details that would not be open to question. All evidence is to be tested. Opposing lawyers test evidence before a judge and jury. Scientists publish papers critical of other evidence. Evidence testing is dynamic. Paul’s evidence had to be meticulous. He was painfully aware of having dedicated, informed opponents. His statements about the church of God in Jerusalem, Cephas as leader, James as 2nd leader, the fact of other apostles and, very importantly, his references to “after three years,” and later “after fourteen years.” His opponents must not be able to fault any detail, otherwise he would have been discredited.

So, those opponents are “out of screen” poised ready to point out any error. Although unseen they were “a testing” of the accuracy and integrity of his evidence. It is Paul’s carefully crafted defence of his own apostolic ministry. He dare not make a mistake or exaggerate or his opponents will discredit him.

So, this is evidence designed for another purpose: Paul’s own defence back then. For us it is “raw” evidence that has the effect of assuring us of the factual basis of the church in Jerusalem, and its Faith.

FINALLY

We need to be aware of the objective in this era of unbelieving Postmodernism. It doesn’t matter what various modern-day sceptics say, the evidence for Christian origins is there, evidence that is credible for a reasonable person to accept as the conscientious basis for Christian faith.

Bishop Paul Barnett is the former Bishop of North Sydney and has lectured at Moore College for many decades. He is the author of many books and is married to Anita.

Editorial Spring 2024

- Details

- Written by: Gavin Perkins

In its 2018 report An Evangelical Episcopate, the Sydney Diocesan Doctrine Commission helpfully elucidated the core responsibilities of a Bishop in the Anglican Church. The first priority of a Bishop is to be a guardian of ‘the faith that was once for all delivered to the saints’ (Jude 3). This is the priority found in the New Testament and in the Anglican Ordinal. Through public proclamation and defence of the apostolic gospel and by personal example the bishop is to do all in his power to ensure that the teaching of Scripture shapes and directs the life, ministry and mission of his Diocese. Other priorities flow from this. The Bishop must order the ministry of the Diocese towards this gospel witness and ministry, he must exercise pastoral concern and insight, he must represent his Diocese faithfully nationally and internationally, and he must administer the work of the Diocese in line with its mission. This is the vital and onerous task of each Bishop and so we must remain deeply committed to pray for our Bishops, and we rejoice in great thankfulness for those who have and continue to discharge these duties. In this edition of Essentials, it is wonderful then to have three such faithful Bishops represented as contributors. In a global and national Anglican context in which Bishops have often been at the vanguard of heterodoxy rather than orthodoxy, it is a great joy to hear from these three brothers, Peter, Kanishka, and Paul in this edition.

Alongside these contributions we have our eyes lifted to see the work of ARDFA amongst some of the most distressed displaced peoples, holding out the love of Christ in the darkness, and we also have our minds stimulated to see with clarity the glory of Jesus’ transfiguration and its purpose for his ministry. I commend our Spring edition to evangelical Anglican friends across Australia.

GAVIN PERKINS, BOWRAL NSW

EDITOR

From the Border: Bearing Fruit from Burden

- Details

- Written by: Jessica Boone

From the Border: Powerful Partnerships Bearing Fruit from Burden

From the Border: Powerful Partnerships Bearing Fruit from Burden

Powerful partnerships between Anglican churches are bringing Christ’s love to some of the most vulnerable communities.

Since the military coup in February 2021, fighting has intensified in Myanmar between the military and insurgents. It continues to have widespread, devastating effects across the country, including severe economic hardship, shortage of health services, and people unable to meet their basic needs. These hardships are particularly acute for the Karen minority, a marginalised Christian people group who also face persecution and have few options for earning an income. Karen and Karenni states have seen some of the most intense levels of fighting, displacement, and humanitarian need in the country.

There are tens of thousands of Karen people internally displaced in Myanmar or living as refugees along the Thai-Myanmar border. New waves of refugees are prompted by flair-ups in the fighting and aerial strikes. Many flee into the jungle and then make their way to refugee camps like Mae La for safety. Mae La is the largest of nine refugee camps in Thailand, hosting around 34,000 refugees of all religions.

Through ARDFA, churches from the Melbourne and Bendigo Dioceses, and St. Alban’s in WA, have been loving the Karen people in their plight, supporting the Diocese of Hpa-an in partnership with the Mothers Union (MU) and Karen Anglican Ministry at the Border (KAMB), a group of churches established on the Thai- Myanmar border area by Anglican evangelists. KAMB aims to show Christ's love as they help people in need, so as to “bear one another’s burdens and so fulfil the law of Christ” (Galatians 6:2).

Though their resources are limited, KAMB has worked tirelessly to bring relief to those displaced along the border, including remote areas of the jungle, who often lack food, clean water, and other essentials. They also play a major role in caring for new refugee arrivals into Thailand, many of whom experience trauma and are left desolate after having to flee their homes so quickly. These new arrivals come with very little yet need to be able to support their families to survive.

These ministries move beyond simply meeting immediate needs. They’re also securing more lasting and holistic transformations and building sustainability in the lives of the Karen. In Myanmar, ARDFA’s plantation project in the remote village of Htee Ka Haw has provided the local people with the resources they need to generate income. In Thailand, land was purchased for St Luke’s Toh Ta Anglican Church with help from the Bendigo Cathedral. ARDFA raised funds to build a kitchen and dining hall that is serving the church and its community. The annual School of Biblical Theology Conference has seen Karen Christians strengthened for ministry with training in preaching, leadership, and teaching, assisted over the years by the Rev Marc Dale and other visiting teachers from Australia.

By helping new arrivals in Thailand to start microenterprises, refugees are empowered to provide for their families, become self-sustaining, and maintain their independence and dignity.

Naw Kyi Kyi Win rejoices that, “by the grace of God, the project is going well! As we help the people in need, we serve the Lord.” She is one of the many Christians who are serving the refugee community through the New Arrivals Project.

From his recent visit, the Rev Marc Dale from St. Alban’s Anglican Church, WA, reports that “when they arrive they get a month of food and capital… People have been set up with animal husbandry; weaving has been successful too. There are many food stalls - the camp is so big, it is its own economy!” In this bustling camp, Naw Toe Pwae’s ducks are multiplying. Meanwhile, Naw Mu Phaw received 500 Baht ($20 AUD) for one shirt that she had woven, which is helping to meet her family’s needs. On the profits of his family’s weaving, Saw John Htoo Say was able to build a house. Saw Poe Law Eh bought a guitar with his start-up capital and now has 20 people attending his music class.

Some of his students are now serving in the church worship band. Saw Nu Say is making cement stoves and selling them. Naw Ray Htoo attempted to expand her shop to sell drinks. It worked, and now she is sewing clothes as well, having leased a sewing machine from St. John’s MU for 200 Baht.

Life in a refugee camp is difficult for anyone, but for people with a disability, the challenge is compounded. Tragically, when he was just one month old, Saw Eh K'tu Moo (now 28) became very sick and lost the use of his legs. He walks on his knees and uses both hands to move about. Using the toilet is most difficult, as he has to go downstairs and outside. It is particularly hard for him during the rainy season. Our partners at St. John’s church report that, “his mother brought him to Mae La for safety as he cannot run when something happens. She went back to Myanmar to bring the other children."

The next development in ARDFA’s work is to improve the daily lives of refugees with disabilities. Support includes nutritional food, toiletries, medication, disability aids, accessible toilets suited to their needs, and assistance to attend regular medical appointments. Yet, amongst the hardship, ministry is fruitful and there is much to praise God for. The vulnerable are being cared for by brothers and sisters they’ve never met. Christians are supporting and serving one another as they rebuild their lives. Churches are being strengthened and evangelism is everywhere. People are coming to faith and are being baptised. Refugees are turning to Christ as they encounter Christians, witness their faith, and receive gospel-motivated love. Please keep Myanmar, its people, and our partners in your prayers.

Jessica Boone,

Anglican Relief and Development Fund Australia