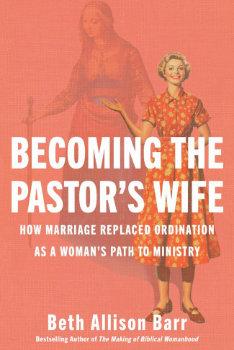

Becoming the Pastor’s Wife

Becoming the Pastor’s Wife

BETH ALLISON BARR

Brazoz Press, 2025

Reviewed By Alexandra Phillips

Herself a pastor’s wife and historian, Beth Allison Barr challenges the contemporary Southern Baptist Convention (SBC) notion of ‘pastor’s wife’ from within. Her book is a timely, welcome contribution to conversations on the role of women in leadership. Barr questions the wisdom of narrowing the pastor’s wife role to supporting a husband’s ministry, and argues its recent evolution is associated to the decline of female ordination. Whilst offering a leadership opportunity for some women (albeit subordinate), the pastor’s wife role deauthorises women’s independent leadership. Barr persuasively objects to this being considered a biblical role, noting the Bible’s silence on the role performed by wives of ministering husbands, like Peter’s wife. Barr also protests the claim that alternative church leadership roles for women are nonbiblical, pointing to women with authority like Prisca and Junia, whose ministry shows no signs of dependence on a husband in ministry. Likewise, she reveals historical women in church leadership. Barr builds her case compellingly through chapter after chapter of illustrative stories arising from an eclectic mix of history, a survey of ‘pastor’s wives’ literature and her personal experience, inviting the reader’s reactions along the way.

As a historian, Barr complexifies statements about women’s ordination across the ages. She notes its contemporary understanding is a recent development, disagreeing with powerful SBC leaders like Al Mohler (president of the Southern Baptist Theological Seminary). Though Barr’s flow within chapters is occasionally convoluted as she overdoes suspense or draws out her evidence, she ably holds a wide gaze on history by contrasting women’s ministry and ministry titles from different time periods. From the early church-fifth centuries, she uses archaeological evidence to tell of women in church leadership, including performing the eucharist. Next Barr concludes mid-seventh century female superior, Milburga, had a comparable position to a bishop, in her rule over a double monastery (monks and nuns). Then Barr neatly explores how ordination reforms in the 10th-12th centuries linked it to the powerful position of performing the eucharist, requiring a sexually pure unmarried male priest. As medieval priests hardly pursued sexual purity, the result was the debasement of women. Later, though male protestant reformers married, they kept a position of ‘masculine authority’ gained from having an exemplary wife, which led to the origin of the subordinate pastor’s wife position.

Barr then rigorously examines SBC history, demonstrating the influence of particular people, events and resolutions that rapidly and recently turned the tide on the SBC position. Where it previously recognised women’s ministry, both through ordination and just payment, it then defunded churches with female pastors. Barr records Dorothy Patterson’s sway, pushing the complementarian agenda for the white evangelical pastor’s wife, through seminary lessons in which wifely submission was presented as the woman’s highest calling (including training on packing a husband’s suitcase, housekeeping and sex). Far from agreeing that women’s pursuit of church leadership is culturally influenced, Barr suggests capitalism and the 19th century rise in domesticity of women’s work as influential to the SBC notion of the pastor’s wife. As ‘godly woman’ became equivalent to ‘good wife’, she draws the parallel to ‘women in ministry’ becoming ‘wife of a minister.’ Barr clearly establishes links between the growth in submission language in pastor’s wives’ literature and the complementarian Danvers statement (1989), Piper and Grudem’s book Recovering Biblical Manhood and Womanhood (1991) and the ‘submission statement’ (1998) added to the SBC confessional document. She uncovers how the recategorization of ministry workers for tax exemptions led unwittingly to controversy over women’s ministry titles, positions and payment. Thus, as women’s independent path to ministry became more difficult, the pastor’s wife model of service ‘covered the absence of female pastors.’ This resulted in the loss of authority of women’s leadership, and women’s leadership becoming subordinate by definition.

Though Barr regrets the bleakness of the SBC trajectory she uncovers, she closes with stories of hope from church history and the not-too-distant SBC past. She also provocatively suggests that if the white church’s pastors’ wives modelled themselves on the black church for a change, this might lead to a truer opportunity for women to minister with spiritual authority and recognition.

Becoming the Pastor’s Wife is a stimulating read, informing how recent developments have shaped the (widely influential) SBC complementarian concept of the pastor’s wife. This serves as a case study beyond the SBC, and should prompt the church to re-evaluate biblical foundations and historical claims made of the ‘pastor’s wife’ and women in church leadership.

Alexandra grew up in Chile in a missionary family as a pastor's daughter. Since moving to Melbourne, she has studied history, literature, theology and teaching. She is a pastor's wife and mother of two daughters.

7