Ben Underwood asks how Christians will respond to the way our society is thinking about homosexuality.

The youth minister at my church invited me to talk to the youth group about homosexuality from a Christian perspective. I think this is a serious topic, and since it is difficult to turn on the TV or read the paper without encountering something to do with homosexuality at the moment, it also seems to me that we should be thinking and talking about it in our churches. So, having done some renewed reading in the area, I went along to then youth group and talked for just under an hour about homosexuality to the upper high schoolers. Apparently they had never been so attentive. The following article is a (grown-up) version of that talk.

What is homosexuality?

Homosexuality is a complex thing. There is homosexual behaviour, that is members of the same sex engaging in sexual practices with one another. But prompting sexual behaviour is sexual desire, and so homosexual desire, sexual desire for members of the same sex, is the inner part of homosexuality. A small minority of people experience homosexual desire, and a smaller minority experience homosexual desire consistently and persistently and may be said to have a homosexual orientation.1 Some of those who experience same-sex attraction may take on a gay or lesbian (or bisexual or transgender) identity and join the lesbian, gay, bisexual and traSnsgendered (LGBT) community. But not everyone who experiences homosexual attraction or orientation chooses to do this. In short, homosexuality is a complex thing potentially involving desire, orientation, socio-cultural identity and sexual practice.

How is our society thinking about homosexuality?

Much of this will be no news to you, but over the last generation our society has been subject to determined campaigns for a moral reassessment of homosexuality. Whereas homosexual behaviour had been considered unacceptable, because it was sinful or perverted and revolting (or both), all that has changed. Homosexuality has been decriminalised, normalised, affirmed and in many ways celebrated as a legitimate and natural state for someone to inhabit. This movement by and for homosexuals has been carried on in the arenas of science, law, the arts, entertainment, the media and even advertising campaigns.

In science homosexuality has moved from being perceived as a rare psychopathology that may be treated, to being perceived as a not-uncommon, biologically-determined condition, not amenable to change. In legislation, Australian states and territories repealed sodomy laws between 1975 and 1997. These legal reforms by no means signalled approval of homosexual practice for all who voted for them.2 But decriminalisation was only a first step towards the legal recognition of homosexual persons and partnerships. Today in Western Australia where I live, gay couples are regarded the same as de facto heterosexual couples. They can adopt, use IVF, inherit, transfer property and access medical services in the same way as heterosexual de facto couples. Anti-discrimination legislation is in place. Some other states have registers of same-sex relationships, and across Australia, campaigns to have same-sex marriage passed into law are in full swing.3

“ Study and discussion of the realities of human sexual experience and behaviour is a good thing.

Christians should not fear the facts.

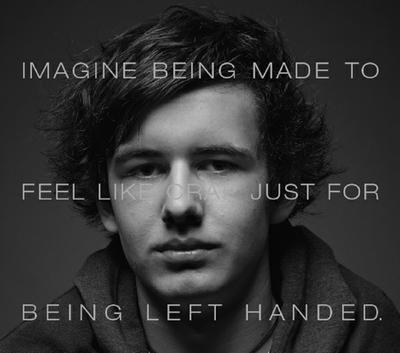

Gay characters sprout up in film, TV shows and books, celebrities and sports stars come out as gay, mistreatment of homosexuals is widely reported as part of the push to stir our indignation and sympathy on behalf of those whose health, safety and freedom are threatened by those who hate homosexuals. Homophobia, like racism, is presented as an evil that must be driven out of our midst. Recognising that homosexual orientation may still attract a social stigma, and that it is also associated with a higher risk of anxiety, depression, substance abuse and suicide, especially amongst teenagers, a recent campaign, a poster in a bus shelter near me, summed up the cause when it invited us to ‘imagine being made to feel like crap just for being left handed.’ The poster on a local bus shelter went on to say that ‘being gay, lesbian, bi, trans or intersex is no different to being born left handed, it’s just who you are. So stop and think because the things we say are likely to cause depression and anxiety.’4 Here are many elements of the modern narrative about homosexuality: you are born that way, you can’t help it and can’t change and yet suffer because insensitive people say things that tell you there’s something wrong with who you are. And it’s all as irrational as making left-handers stop using their left hand. So let’s get rid of this stigma, and welcome gay, lesbian, bi, trans and intersex people into the human race.

There are at least three good things in all this. Firstly, study and discussion of the realities of human sexual experience and behaviour is a good thing. Christians should not fear the facts. Secondly, decriminalising homosexual behaviour between consenting adults is better than prosecuting it in courts. Even if one judges such behaviour to be immoral, not all immorality is, nor need be, a criminal offence. Laws are not needed to kerb the spread of homosexual behaviour in our society—most people are happy with their heterosexuality, and not rushing to try homosexual sex. And thirdly, opposing the hatred and violence with which some may respond to homosexuality is an excellent thing. We are to love our neighbours, and that involves protecting our homosexual neighbours from those who hate or despise them. They participate with us as full members of the human race.

There are at least three good things in all this. Firstly, study and discussion of the realities of human sexual experience and behaviour is a good thing. Christians should not fear the facts. Secondly, decriminalising homosexual behaviour between consenting adults is better than prosecuting it in courts. Even if one judges such behaviour to be immoral, not all immorality is, nor need be, a criminal offence. Laws are not needed to kerb the spread of homosexual behaviour in our society—most people are happy with their heterosexuality, and not rushing to try homosexual sex. And thirdly, opposing the hatred and violence with which some may respond to homosexuality is an excellent thing. We are to love our neighbours, and that involves protecting our homosexual neighbours from those who hate or despise them. They participate with us as full members of the human race.

But the moral reassessment of homosexuality that is being recommended overturns Christian teaching about homosexuality. Some in the churches are ready to do this, and to incorporate the new account of homosexuality into Christianity. But overturning the received Christian teaching about homosexuality means reinterpreting or rejecting several biblical passages upon which the Christian resistance to sanctioning homosexual desire and behaviour is based. It is all very well to rethink how we have interpreted certain biblical passages in light of what we learn through investigating the world, but we should first make sure our science is good. And we should also remember that science can’t make a moral assessment of homosexuality for us. The road from what is to what should be is not so simple as saying since people don’t choose to be homosexual, they should not be discouraged from acting upon their desire for homosexual relationships.

What does science really say?

Are people born gay or do they choose to be gay?

The use of left-handedness as an analogy to homosexuality is an interesting one, because, if you are anything like I was, you might think that handedness is genetically determined, that your genes code for your handedness. But actually I discovered that it is not so. Identical twins are genetic clones, and yet 18% of identical twins have different handedness.5 Genes are not destiny when it comes to handedness. Other factors are at play. For at least some people handedness is acquired somehow during the history of their development. This is not to say that there is no genetic influence involved, it is just to say that genes are one factor in a complex of interacting factors which give rise to each individual with his or her individual characteristics.

Something similar could be said of homosexuality. It is a complex thing and plenty of scientists and scientific studies suggest that genes do not make you gay, but seem to have some influence. Not all identical twins share orientation, in fact it is more common for the identical twin of a homosexually oriented twin to be heterosexual.6 Genetically identical individuals do not necessarily have the same sexual orientation. Sexual orientation is formed by factors in addition to genetic inheritance. Francis Collins, head of the Human Genome Project says that the contribution of genes to homosexuality is ‘a pre-disposition, not a pre-determination.’7

This does not mean that a simple choice does not make you gay. As N. E. Whitehead points out ‘two thirds of the ages of first (same-sex) attraction are in the range 6–14 years.’ And he comments, ‘At that age no-one chooses lifetime sexual orientation or lifestyle in any usual sense. Same-sex attraction is discovered to exist in oneself rather than chosen.’8 What other factors might influence the development of same-sex attraction? There are investigations into how environmental factors, from hormones in utero to childhood experiences and relationships, might have some influence in the emergence of same-sex attraction and homosexual orientation.9

And choices may not be irrelevant. Observing and understanding the effects of individual choices is enormously difficult. This makes it difficult to demonstrate the role our choices play in who we are today and might be tomorrow. Equally it makes it difficult to deny that an individuals’ choices may have played an important role in making them who they are.10 The question Are people born gay or do they choose to be gay? misunderstands the complexity of the causes of the homosexual condition. People are not born gay, in the sense that that have genes that make them gay, like they have genes that make their skin white or their eyes brown. Nor do people choose to be gay in the sense that they felt they were free to choose to develop homosexual desires or not. Rather, the best of our current understanding is that genes, environment and perhaps individual responses to their circumstances all contribute to the way that same-sex attraction or homosexual orientation arises. But there is plenty we still don’t understand.

Can sexual orientation change?

It’s commonplace to hear the claim that homosexual orientation can’t change, and if your genes make you gay you might expect that to follow as a straightforward corollary. Yet there are people who say that their sexual orientation has changed. Christopher Keane has written his story of experiencing same-sex attraction from an early age, entering a homosexual relationship in his teens and embracing the gay lifestyle in Sydney for fifteen years, before becoming disillusioned with what such homosexuality did and failed to do for him.11 He decided to leave the homosexual scene and return to living out the Christian faith he had first adopted in his teens. Although he expected this to mean celibacy, as he did not expect to experience a change in sexual orientation he did discover both a diminishment of his homosexual attractions and the emergence of lasting heterosexual attraction. In Keane’s view, his determined pursuit of God led to him dealing with the ‘wounds, hurts and deprivations’ of his past with God’s help, and this dealt with the roots of his homosexuality, which lay in the character of family relationships, certain wounding experiences, and decisions of his about where he would meet felt needs.12

Can we add to personal testimony a scientific take on the possibility of change in sexual orientation? Stanton Jones and Mark Yarhouse addressed this controversial question in Ex-Gays? A Longitudinal Study of Religiously Mediated Change in Sexual Orientation.13 The percentage of those reporting successful change is quite modest, but Jones sums up the study’s finding saying, ‘I conclude that homosexual orientation is, contrary to the supposed consensus, sometimes mutable.’14

Does the moral come from the story?

We have seen that there is reason to question the claim that once gay, you’re always gay because you were born that way. But let’s suppose it is in fact the case that homosexuality was inborn and immutable. Does it follow that we cannot censure people pursuing the fulfilment of their homosexual attractions? Does it follow that we must affirm homosexuality as a good thing?

As a culture we do censure people pursuing certain sexual attractions, whatever their origins might be. Incestuous attractions, for examples, or paedophilic attractions are regarded as attractions that should not be embraced or acted upon. We make this negative moral judgement without reference to the causes of the attraction. Paedophilia is a lifelong orientation of sexual desire with an onset even from puberty, that is difficult to change, and seems to have biological factors in causation, including genetic factors.15 Yet even though it may be true that paedophiles do not choose the orientation of their desires and cannot change them easily (if at all), we still expect them to resist those drives and classify them as a sexual disorder. This is because our moral judgement on paedophilia is based on the harm we see visited upon children when paedophiles do act out what they desire.

It seems to me that in fact our moral reappraisal of homosexuality is more about us judging that homosexual relationships between consenting adults are not harmful to anyone, and are in fact a fulfilling experience for homosexuals that no-one has any reason to deny them. If it is possible to be a happy, well-adjusted homosexual, why not let homosexual people give it their best shot if they see fit to try? Whether you were born gay or became gay, whether you could change or not become rather irrelevant then, because when we make our moral judgements on a calculus of harm minimisation, fulfilment maximisation and personal autonomy, there seems no justification for not letting gays be gay. The point is not that they can’t help it, rather the point is that it’s not hurting anyone. And even if you think it’s hurting them, who are you to tell them how to live their life?

We can see that if the story is ‘gays are born that way’, and ‘once gay always gay’ the moral does not follow. But if the story is ‘it’s ok as long as you’re not hurting anyone’, and ‘what happens between consenting adults in the bedroom is their business and no threat to anyone else’, and ‘everyone should be free to follow their heart’, then the moral starts to follow more obviously. The trouble is that Christians aren’t sold on that story. We decide moral questions in another way, guided by the gospel of Jesus, as given by God in the Bible.

What does the Bible say?

Is being gay sinful?

To think Christianly about homosexuality with its dimensions of attraction, orientation, behaviour and socio-cultural identity we need to set these in a Christian account of human sexuality in creation, fall redemption and recreation. So here’s a brief attempt at this.

God is our creator and he has an intended order for his creation. As it touches our sexuality, here’s Jesus:

‘[A]t the beginning of creation God “made them male and female.” “For this reason a man will leave his father and mother and be united to his wife, and the two will become one flesh.” So they are no longer two, but one flesh. Therefore what God has joined together, let no one separate.’ (Mark 10:6–8, niv)

That is to say that the sexual difference of male and female and their sexual union in marriage is what God has ordained. This leaves two places for human beings to inhabit: faithful sexual union in marriage, and abstinence from sexual relationship outside marriage.

To our world this binary absolute may seem unrealistic and unhealthy, and perhaps these days nobody really believes Christians might believe that, much less live it out. And yet that is the foundation the Bible lays. Part of the reason this may seem unrealistic is that our sexual desires hardly line up with this demand. It seems to me that we don’t find our sexual desires simply awakened by one other person of the opposite sex, whom we marry and remain exclusively attracted to, while the rest of the race leaves us cold. Rather, for most, our sexual desires are awakened as teenagers and we experience all sorts of attraction to all sorts of people, and while our love for and attraction to any spouse we might have might remain strong and deep, it might also wax and wane, and others might turn our heads, either occasionally, or even pretty constantly! Those who have any sexual desires generally find they need to manage and discipline those desires and learn to express them in ways considered appropriate. And those who decide to explore what happens when you break the usual rules, and explore different sexual territory often find their desires shift and become open to being aroused in all sorts of practices.

The Bible does not imagine that our sexual desire is neatly tailored to heterosexual faithfulness. Another foundation for the Bible’s account of our sexuality is found in Romans 1:21–27 where we read a diagnosis of the human condition as turned, by our refusal to thank and glorify God, to futility, darkness, foolishness and impurity. We are all caught up in this corruption, but the departure from the God-ordained union of male and female found in homosexual practice vividly illustrates the attitude to God’s intentions found in all sin: we turn what God has given us (in this case our sexual bodies) to uses suggested not by God, but by our own blinded and misdirected passions. And, as we do this, we bring upon ourselves our penalty.

Implicit in the use of this example is a rejection of homosexual practice as pleasing to God, and a judgement that homosexual desire is disordered.16 Homosexuality delivers a penalty to those who pursue it. It is not that homosexual behaviour is the worst of sins, but rather that all sin is somehow like homosexual sex.17 Following disordered desires does not lead to human flourishing in the end. This is why Christians regard it as an act of truth and love not to join the movement to affirm and celebrate homosexuality. Because we wish those who experience homosexual desire well, we warn them against following those desires, because of the way the Bible warns about it.

Can I be a Christian and homosexual?

Yes, in the sense that I may put my faith in Jesus, and his death and resurrection, no matter who I am.18 However, a Christian cannot receive homosexual desires and embrace homosexual practice as good and holy things. Neither can a Christian say that being gay is just as fundamental to who I am as being in Christ. Christians are called instead to ‘flee from sexual immorality’ (1 Cor 6:18), and to understand themselves first and foremost as a redeemed person in Christ.19 This is part of the life of repentance and faith.

This does ask those who desire to live as pleases God, who also have a homosexual orientation at least to so manage their sexual desires that they live celibate lives and do not conduct homoerotic relationships. There are others whom the gospel calls to renounce hopes of sexual fulfilment and the companionship of marriage in order to follow Christ—all who are unable to contemplate marriage, because no suitable marriage prospect emerges, perhaps because of a disability or illness they suffer, or a vocation they choose to pursue. Same-sex attracted people are not singled out as the only ones denied marriage, and sex, by their circumstances. And there is life and contentment even without sex. Love is bigger than simply love within sexual relationships.

Yet the gospel is not at heart a stern call to ‘renounce your bad desires if you know what’s best for you’. The gospel is news of God’s love demonstrated in the redemption of the world through the death and resurrection of Jesus. The gospel is an invitation to new life, to a relationship with God through Jesus Christ. And in that relationship is peace, joy, love, hope, grace, healing, wisdom, help, comfort, purification, acceptance, reconciliation, strength, transformation, forgiveness, life and whatever we might need, if we seek it and patiently wait for it. 1 Corinthians 6:9–11 speaks of sinners, including ‘men who have sex with men’ being ‘washed…sanctified…justified…by the Spirit of God.’ This a reality that changes you, not a mere teaching. It might be difficult to put to death the flesh—Paul’s theological term for the inner source of our misdirected and impure desires—but it is not done without the help of God’s Spirit indwelling us and imparting God’s love and peace to us in the midst of it all.

All this is to say that Christians who renounce pursuing the fulfilment of their same-sex attractions are setting aside one hope (the hope of love in a committed, romantic, sexual relationship) in order to embrace what they trust will prove to be a better one (knowing God through his love and salvation in Christ). And Christians who renounce a gay identity in a gay community are setting aside one self-understanding and a related belonging, to embrace a different self understanding (‘I am God’s beloved child in Christ, I am his and he is mine even now, and he will bring me, transformed, to glory forever in the new creation’) and a different belonging (I am a full, valuable, known and loved member of Christ’s church and its expression in the relationships of Christians, especially my local congregation). This a spur to us to take the inclusive and caring community in our churches as seriously as we know how.

I conclude by sticking my oar in briefly in answer to some last questions. There’s plenty more to grapple with in these issues which frame and dominate many people’s lives, both in and out of the churches. May the Lord teach us to deal with others fairly, graciously, patiently and faithfully in these matters.

Should we have gay marriage?

Obviously since the Bible makes a negative judgement of the goodness and holiness of homosexual practice, to affirm and encourage same-sex attracted people in such relationships by recognising homosexual marriages does not make sense from a Christian perspective. However, once you have decided that there is nothing morally wrong with homosexual relationships, it makes perfect sense to normalise and stabilise them in the same way as heterosexual relationships are normalised and stabilised, not least by the public and legal covenant of marriage administered by the state. And inasmuch as homosexual communities suffer from higher rates of relationship churn, and mental illness, substance abuse etc, it is hoped that including such relationships in the mainstream of marriage will lead to improvements in such indicators of dysfunction, as those who were outcast are brought within the fold.

No-one knows whether this will happen. If it goes ahead, it will be a social experiment. It may substantially ameliorate the situation of homosexual people, or not. The Bible suggests that in the end it will not be good for homosexual people or society (although perhaps not in any immediately obvious way). But quoting the Bible is hardly persuasive to those who regard it as a discredited and outmoded book. Since Christians have Christian moral reasons for doubting the moral reassessment of homosexuality, we shouldn’t use other reasons (moral or otherwise) to try. It makes us seem like we are not really saying why we are taking this position if we just talk about slippery slopes or the health of homosexual communities. Fundamentally we need to be upfront about our gospel reasons not to support the cause.

Since we live in a democracy, if our voice and our vote does not win the day, that’s the way it goes. Life and Christian witness will go on. We should be gracious if we are defeated and not suffer defeat as if we were somehow entitled to victory in this matter.

What should I do if someone tells me they have homosexual feelings?

Listen, take them seriously, be their friend. Talk to them about it if they want. Find out some more and think about it so you can be of help to them.20

What should I do if I have homosexual feelings?

Don’t panic. Your life is not over. There is a difference between experiencing some attractions, having a persistent and consistent orientation towards the same-sex. attraction and identifying yourself as ‘gay’, ‘bisexual’, ‘lesbian’, etc.

You are not alone. There are others in your situation and people you can talk to, books you can read, if you reach out for such help.21

How do you talk about homosexuality and homosexuals?

Do you think about the fact that this is quite possibly a real and troubling issue for people around you, and especially for people at your church too? Or do you assume that no one you know is homosexually attracted? Do you think about the way you talk and joke about homosexuality and homosexuals? Does your talk and the atmosphere it creates make it harder or easier for same-sex attracted people to reach out with confidence and get help to figure out what they are going to do with these experiences?

Therefore, I urge you, brothers and sisters, in view of God’s mercy, to offer your bodies as a living sacrifice, holy and pleasing to God—this is your true and proper worship. Do not conform to the pattern of this world, but be transformed by the renewing of your mind. Then you will be able to test and approve what God’s will is—his good, pleasing and perfect will. (Rom 12:1–2, niv)

Ben Underwood oversees the 5pm congregation at St Matthew’s Shenton Park in Perth. He is married to Michelle and they have two (delightful) children. Ben grew up in Sydney, studied science at university and taught mathematics before becoming a minister. He has been on staff at St Matthew’s since 2009.

1 Jones and Yarhouse quote the following figures from a 1994 study by Laumann, Gagnon, Michael and Michaels: 6.2% of males and 4.4% of females report experiencing attraction to members of the same sex; 2.0% of males and 0.9% of females identified themselves as having a homosexual orientation. Stanton L. Jones and Mark A. Yarhouse, Ex-Gays?A Longitudinal Study of Religiously Mediated Change in Sexual Orientation (Downers Grove: IVP Academic, 2007), 32.

2 Indeed the preamble to the 1989 WA legislation begins, ‘WHEREAS, the Parliament does not believe that sexual acts between consenting adults in private ought to be regulated by the criminal law; AND WHEREAS, the Parliament disapproves of sexual relations between persons of the same sex’ (www.austlii.edu.au/au/legis/wa/repealed_act/lrosa1989392/preamble.html, cited 5 June 2013).

3 See, for example, the Wikipedia article ‘LGBT rights in Australia’ at en.wikipedia.org/wiki/LGBT_rights_in_Australia, and www.australianmarriageequality.com

4 See the campaign run by the depression and anxiety support organisation Beyond Blue at lefthand.org.au

5 David E. Rosenbaum, ‘On Left-Handedness, Its Causes and Costs’, TheNew YorkTimes, 16 May 2000 (partners.nytimes.com/library/national/science/health/051600hth-genetics-lefthanded.html)

6 Whitehead reports that ‘from six studies (2000–2011): if an identical twin has same-sex attraction the chances that the co-twin has it too, are only about 11% for men and 14% for women.’ N. E. Whitehead, ‘Common Misconceptions About Homosexuality’ (www.mygenes.co.nz/myths.pdf, cited 6 June 2013). See also Stanton L. Jones, ‘Same-Sex Science’, FirstThings220 (2012), 27–33 (www.firstthings.com).

7 Quoted in Michael Bird and Gordon Preece (eds.), Sexegesis (Sydney South: Anglican Press Australia, 2012), 13.

8 Whitehead, ‘Common Misconceptions’.

9 Jones (‘Same-Sex Science’, 29) reports that ‘Recent studies show that familial, cultural, and other environmental factors contribute to same-sex attraction. Broken families, absent fathers, older mothers, and being born and living in urban settings all are associated with homosexual experience or attraction.’ Jones goes on to say, ‘Of course, these variables at most partially determine later homosexual experience, and most children who experienced any or all of these still grow up heterosexual, but the effects are nonetheless real.’

10 Hence Jones says, ‘Human choice may be viewed legitimately as one of the factors influencing the development of sexual orientation, but this “is not meant to imply that one consciously decides one’s sexual orientation. Instead, sexual orientation is assumed to be shaped and reshaped by a cascade of choices made in the context of changing circumstances in one’s life”.’ Stanton Jones, ‘Sexual Orientation and Reason’, an expanded version of ‘Same-Sex Science’ published at www.wheaton.edu (2012), 11, quoting W. Byne and B. Parsons, ‘Human Sexual Orientation: The Biologic Theories Reappraised,’ Archives of General Psychiatry 50 (1993), 228.

11 Christopher Keane, Choices: One person’s journey out of homosexuality (Brunswick East: Acorn, 2009)

12 Keane, Choices, 61, and the personal stories in Christopher Keane (ed.), What Some of You Were (Kensington: Matthias Media, 2001).

13 Their work has now been updated as ‘A longitudinal study of attempted religiously mediated sexual orientation change’, Journal of Sex and Marital Therapy 37 (2011), 404–427; see also www.exgaystudy.org

14 Jones, ‘Sexual Orientation and Reason’, 11.

15 James M. Cantor, ‘Is Homosexuality a Paraphilia? The Evidence For and Against’, ArchivesofSexualBehaviour 41 (2012), 237–247, and Katarina Alanko et al, ‘Evidence for Heritability of Adult Men’s Sexual Interest in Youth under Age 16 from a Population-Based Extended Twin Design’, The Journal of Sexual Medicine 10 (2013), 1090–1099.

16 There are those who would dispute that Romans 1 condemns faithful, committed homosexual relationships between those of homosexual orientation, and others who argue that the gospel updated by a modern understanding of homosexuality calls us to move beyond the biblical censure to a new Christian embrace of faithful, committed homosexual relationships. I don’t have space to take up these debates here.

17 Richard B. Hays, TheMoralVisionoftheNewTestament (New York: HarperCollins, 1996), 383–389.

18 As it is put in the 1998 Lambeth Conference Resolution 1.10, ‘We also recognise that there are among us persons who experience themselves as having a homosexual orientation. Many of these are members of the Church and are seeking the pastoral care, moral direction of the Church, and God’s transforming power for the living of their lives and the ordering of relationships. We wish to assure them that they are loved by God, and that all baptised, believing and faithful persons, regardless of sexual orientation, are full members of the Body of Christ.’ (www.lambethconference.org/resolutions/1998/1998-1-10.cfm)

19 A point made well in the Church of England Evangelical Council’s St Andrew’s Day Statement, Application I (e.g. www.anglicancommunion.org/listening/book_resources/docs/St Andrew’s Day Statement.pdf).

20 The books I have referred to by Christopher Keane are a good place to start: What Some of You Were and Choices.

21 Liberty Christian Ministries offers support to men and women who struggle with unwanted same-sex attractions (USSA) and to those who have friends, relatives or spouses who have embraced the ‘gay’ lifestyle or have same-sex attractions (www.libertychristianministries.org.au).