Glenn N. Davies

Glenn N. Davies

President of EFAC Australia

John R. W. Stott was a well-known evangelist and apologist in the 1950s, undertaking various university missions in England, while ministering at All Souls' Langham Place, first as a curate (1945- 50) and then as Rector from 1950.

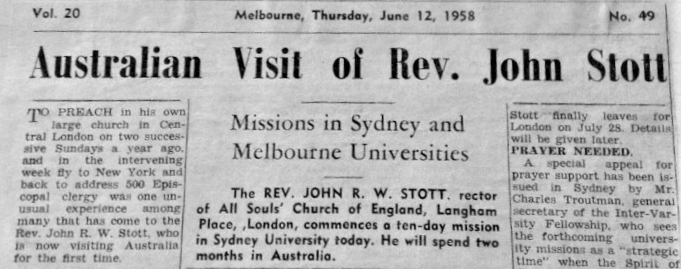

Stott's first visit to Australia was in 1958, the same year that both Basic Christianity and Your Confirmation were published. These were extremely influential books in Australia. The first for Evangelicals of all denominations and the second for Anglican young people in particular, as they prepared for their confirmation. The latter was the standard text for a generation of confirmees.

The purpose of Stott's visit to Australia was to lead university missions in Melbourne and Sydney. One student present at Sydney University's mission recalls that on one occasion Stott had suffered a bout of laryngitis, disabling the projection of his voice to the gathered throng. Yet, as God's grace is perfected in human weakness, this affliction did not prevent the Spirit's work in drawing many students to Christ.

In 1965, Stott returned to Australia, this time not to lead a university mission but to give the Bible studies at CMS Summer Schools in Sydney, Melbourne and Adelaide, as well as to address the Australian Inter-Varsity Fellowship (now knowns as AFES) in Coolangatta. Stott's preaching on 2 Corinthians seemed revolutionary, as an example of expository preaching. John Chapman stated that this visit was a remarkable wake-up call for Evangelicals, especially Anglicans, for empowering ministers to take the text of the Bible seriously and to expound the books of the Bible in a clear and orderly way.¹1 This was in contrast to much preaching which was based on a single text, allowing the preacher to wander along various pathways, however well informed by the general teaching of the Bible, but not a clear exposition of the particular text at hand.2 Stott was to return to CMS Summer Schools in 1971, 1976 and again 1986.

Jonathan Holt captures the importance of John Stott's 1965 visit and its influence on not only Sydney Anglicans, but most Australian Anglican Evangelicals, with these words.

"In conclusion, the emergence of expository preaching in Sydney Anglican Churches may be attributed to the presence of both a fuel and a spark. When John Stott preached at the 1965 CMS Summer School on 2 Corinthians, he inspired John Chapman, among others, to emulate his expository style. Preconditions that enabled the adoption of this expository style were a high view of preaching as proclamation of God's saving activity in Jesus, the development of a Biblical Theology framework for preaching, evangelical engagement in scholarly biblical studies, and a continuing propensity to look to England for leadership. The transformation in the style of preaching from a single-verse as-text to the more systematic lectio continua has had a lasting impact in the Anglican parishes in Sydney and beyond them through the Katoomba Christian conventions.'3

My first experience of hearing John Stott preach was at the Katoomba CMS Summer School in 1971. I can still recall, 50 years later, his measured explanation of the unfolding of "a little while' and "again a little while' expressions in the Upper Room Discourse of John's Gospel. As Edmund Clowney, President of Westminster Theological Seminary, would say: "Stott was the master of sermon construction.' With his refined English accent, he would unravel the complexity of a text with such ease of organisation and in such a memorable manner which penetrated the heart and mind with the very words of God.4 When I heard Stott again at the Urbana Intervarsity Conference in Illinois in 1976, a cartoon was printed in one of the daily bulletins, depicting a student with a Bible under his arm, looking up to the sky with the caption: "I hear God speaking to me in an English accent!'

In 1981, following the success of the first NEAC (National Evangelical Anglican Congress) ten years earlier, Stott was "the star attraction' at the second NEAC held in Melbourne,5 when he delivered an address on Luke 4, entitled the Nazareth Manifesto, once again, Stott's masterful handling of the Lucan account of Jesus' words in Nazareth made its impact on Anglican Evangelicals in Australia. While there was some criticism of this address, in that it promoted social action as the complementary activity of gospel proclamation,6 Stott saw himself in the Evangelical tradition of Wilberforce and the eighteenth-century Evangelical Revival that addressed concerns of social action without neglecting the importance of evangelism. This address, in many ways was the fruit of Stott's significant contribution to the framing of the Lausanne Covenant at the 1974 Lausanne Congress, chaired by Bishop Jack Dain of Sydney.

Much could be said of John Stott's impact on Australia, not least of which being his establishment of the Bible Speaks Today series, which sought to emulate his style of expository preaching; his prodigious writing output which has taught, encouraged and inspired many generations of Australian Evangelicals; and his many visits to Australia. However, for members of EFAC Australia, our very existence owes its origin to John Stott's foresight in 1961, when he along with others established the Evangelical Fellowship in the Anglican Communion, serving as its Honorary Secretary for some twenty years. Many Australians, such as Bishop Jack Dain and Bishop Donald Cameron served on the International Executive, as does Bishop Stephen Hale who currently serves as its chair.

Our Evangelical heritage in Australia owes a great deal to John Stott and it is fitting that we thank God for this impact as we honour his legacy on the centenary of his birth.

NOTES